2.7 — Political Economy of Trade Policy

ECON 324 • International Trade • Spring 2023

Ryan Safner

Associate Professor of Economics

safner@hood.edu

ryansafner/tradeS23

tradeS23.classes.ryansafner.com

Where We’re At

What We’ve Learned:

- Predict & understand why and what countries trade (Trade Models)

- Consequences of trade barriers (tariffs, quotas, subsidies, etc)

- Intellectual history of free trade & protectionist arguments

What’s Left: for good or bad, why do countries have the trade policies they have today?

- A theory of how politics interacts with economics: political economy

Where We’re At

If you agree with the following premises:

- Trade barriers are in general harmful and inefficient on net for a society

- Trade barriers do benefit specific groups of people

We need to answer two questions:

- Why do trade barriers that are often inefficient and welfare-reducing persist?

- How is it possible to get groups or countries to agree to reduce trade barriers?

Political Economy in a Liberal Democracy

Ideal Government & “Naive” Political Economy

People often recommend optimal policies as if they could be installed by a benevolent dictator

- A dispassionate ruler with total control, perfect information, and selfless incentives to implement optimal policy

- A “1st-best solution”

In reality, 1st-best policies are distorted by the knowledge problem, the incentives problem, and politics

- Real world: 2nd-to-nth-best outcomes

Ideal Government & “Naive” Political Economy

Major Actors in a Liberal Democracy

In modern liberal democracies, we can describe four major categories of political actors:

Voters express preferences through elections

Special interest groups provide additional information and advocacy for lawmaking

Politicians create laws reflecting voter and interest gorup preferences

Bureaucrats implement laws according to goals set by politicians

Voters in a Liberal Democracy

Voters express preferences through elections

Voters as economic agents:

Choose: < a candidate >

In order to maximize: < utility >

Subject to: < constraints? >

The Collective Action Problem of Democracy

Citizens vote in politicians to enact various laws that citizens prefer -- and vote politicians out of office if they fail to deliver

A collective action problem: citizens need to monitor the performance of politicians and bureaucrats to ensure government serves voters' interests

The Collective Action Problem of Democracy

Voting is instrumental in enacting voters' preferences into policy

Good governance is a public good: an individual citizen enjoys small fraction of benefit created

Additionally, policies & elections depend on many millions of people

Individual bears a private cost of informing self and participating

Hence, a free-rider problem

The Rational Calculus of Voting

A rational individual will vote iff: p(B)+W>C

B: perceived net benefits of candidate X over Y

- p: probability individual vote will affect the outcome of the election

- W: individual's utility derived from voting regardless of the outcome (e.g. civic duty, "warm glow," etc)

- C: marginal cost of voting

The Rational Calculus of Voting

- A rational individual will vote iff: p(B)+W>C

p≈0

- Outcome requires many votes

B is a public good

- Get small fraction of total benefit

C>0

- Cost of informing oneself and voting informed

The Rational Calculus of Voting

A rational individual will vote iff: p(B)+W>C

If citizens are purely rational, W=0

Citizens then vote if p(B)>C

Prediction: rational citizen does not vote

Voter Turnout: Presidential Elections

| Year | Turnout of Eligible Voters |

|---|---|

| 2020 | 62.0% |

| 2016 | 55.7% |

| 2012 | 54.9% |

| 2008 | 58.2% |

| 2004 | 55.7% |

| 2000 | 50.3% |

| 1996 | 49.0% |

| 1992 | 55.2% |

Sources: Wikipedia, U.S. Census Bureau, Bipartisan Policy Center

The Rational Calculus of Voting

A rational individual will vote iff: p(B)+W>C

Now suppose, D>0

Citizens then vote if D>C

More importantly, the voter votes regardless of the positions of the candidates!

Vote for non-rational reasons: "more presidential looking," "taller," "a better temperament," etc.

The Rational Calculus of Voting

Many do vote, even at significant personal cost!

"Expressive voting": people vote to express identity, solidarity, tribalism, preferences, etc

Voting as a pure consumption good, not an instrumental investment to achieve policy preferences

Rational Ignorance

Model predicts rational ignorance

Not necessarily no voting, but

- Less than maximum turnout

- Voting not for instrumental, ‘rational’ reasons, but for non-rational reasons

Rational Ignorance

Winston Churchill

Winston Churchill

1874-1965

"The best argument against democracy is a five minute conversation with the average voter."

Rational Ignorance

Somin, Ilya, 2014, Democracy and Political Ignorance

Rational Ignorance

Somin, Ilya, 2014, Democracy and Political Ignorance

Rational Ignorance

Just so we’re clear (because election day is near)

This is not a normative statement: that you should/not vote, or that you are a good/bad person

This is a positive explanation of why we see the (...suboptimal) results we see in the world

Special Interest Groups in a Liberal Democracy

Special interest groups: any group of individuals that value a common cause

SIGs as economic agents:

Choose: < a candidate to support >

In order to maximize: < utility >

Subject to: < budget >

The Logic of Collective Action

But power and influence is not evenly distributed across interest groups

Logic of collective action: Smaller and more homogenous groups face lower collective action costs of organizing than larger and more heterogeneous groups

Smaller groups to whom benefit (cost) of a policy is more concentrated can outmobilize larger groups where benefit (cost) is more dispersed

The Logic of Collective Action

- Policies in representative democracies tend to feature concentrated benefits and dispersed costs

Politicians in a Liberal Democracy

Politicians create laws reflecting voter and interest gorup preferences

The politician's problem:

Choose: < a platform >

In order to maximize: < votes >

Subject to: < being re/elected >

Politician's Incentives: Who's Interests To Represent?

Rationally ignorant voters pay little attention to actual substance or policy-making; more to TV-friendly spectacles

Big speeches, ribbon cutting ceremonies, attack ads on rivals, etc

Platforms more about broad platitudes than substance "family values," "tough on crime," "change," "drain the swamp" etc.

Politician's Incentives: Who's Interests To Represent?

Special interests pay very close attention and are actively involved in policy-making and contribute to political campaigns

Politicians allocate funds towards special interests

Politician's Incentives

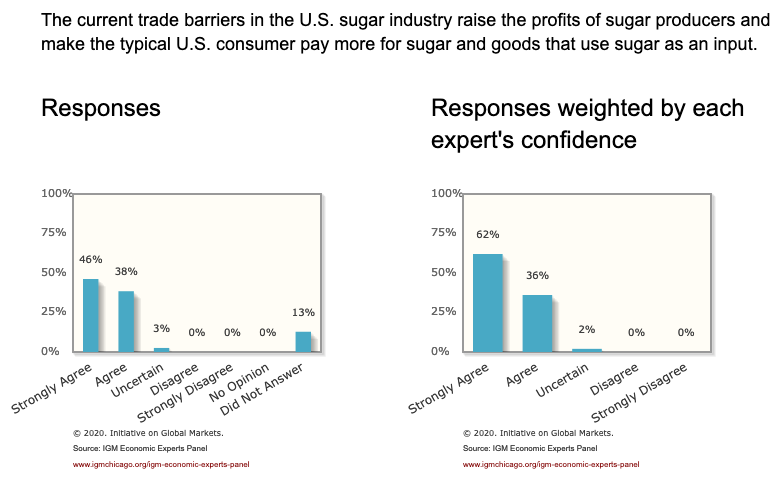

An Example: Sugar Tariffs

An Example

"In fiscal year (FY) 2013, Americans consumed 12 million tons of refined sugar, with the average price for raw sugar 6 cents per pound higher than the average world price. That means, based on 24 billion pounds of refined sugar use at a 6-cents-per-pound U.S. premium, Americans paid an unnecessary $1.4 billion extra for sugar. That is equivalent to more than $310,000 per sugar farm in the United States"

Source: Heritage Foundation

An Example

An Example

An Example

"Washington, D.C., doesn't have many farms, or farmers. Yet thousands of residents in and around the nation's capital receive millions of dollars every year in federal farm subsidies...lawyers, lobbyists and at least one psychologist collected nearly $342,000 in taxpayer farm subsidies between 2008 and 2011...[also] Gerald Cassidy, the founder of one of Washington's most powerful lobbying firms, Cassidy & Associates; Charlie Stenholm, a former congressman; and Chuck Grassley, a Republican senator from Iowa; [and former] Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack..."

An Example

And yet, each individual pays maybe $1-2 a year in higher prices for sugar

Difficult to mobilize voters to petition to end the sugar subsidy to save $1

Sugar producers stand to lose a billion dollars

Sugar PACs that contribute thousands to key lawmakers

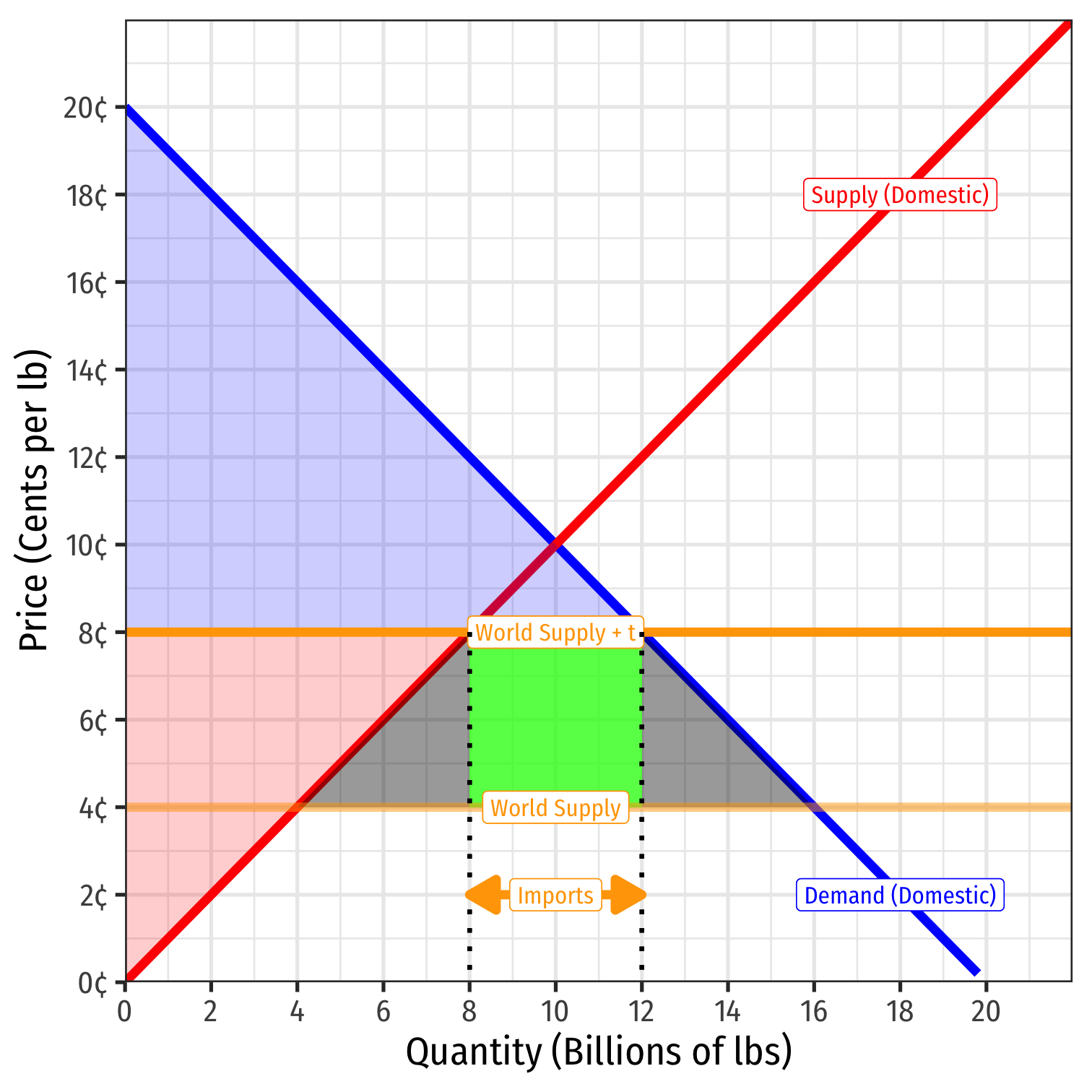

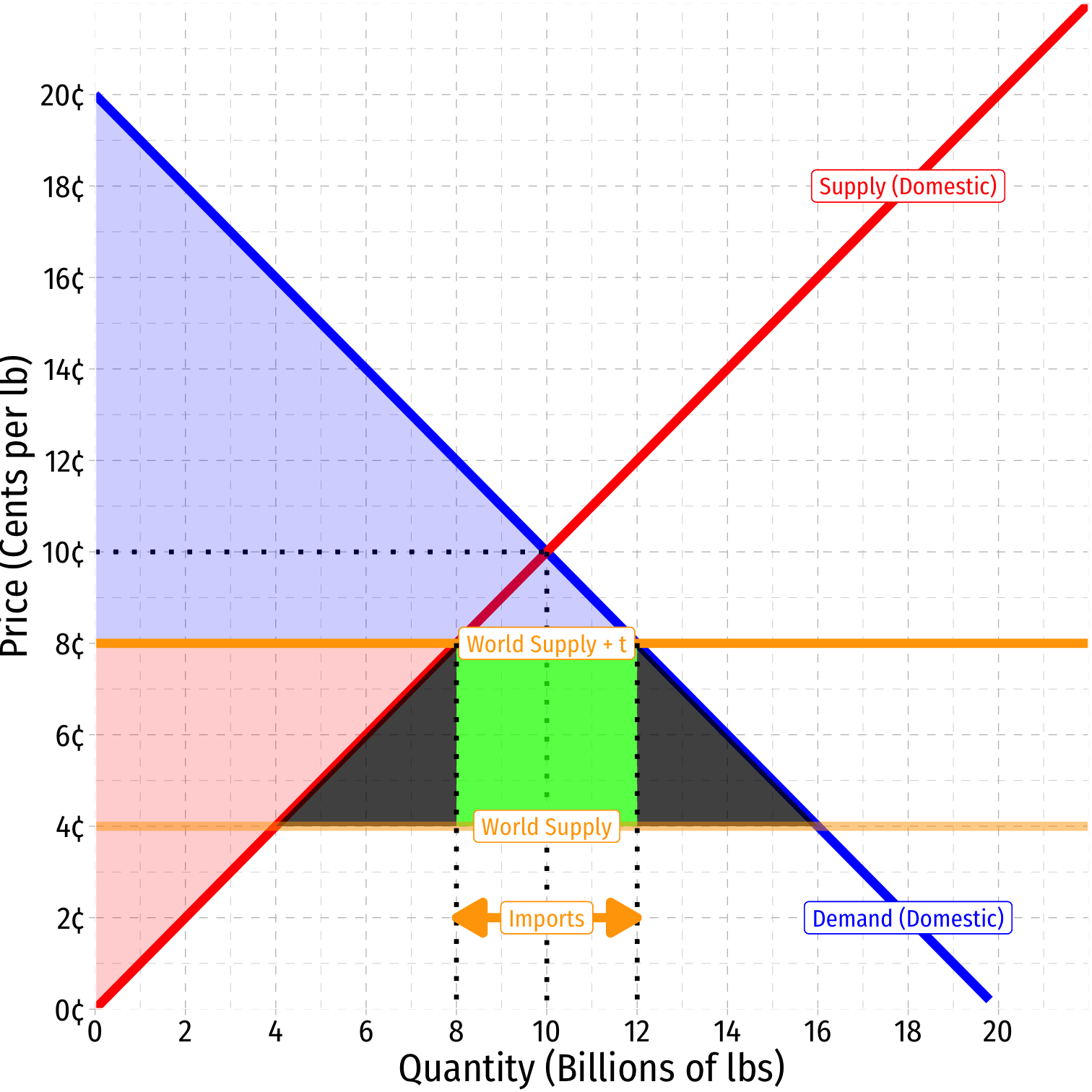

Recall The Consequences of a Tariff (Say on Sugar)

- Domestic consequences of tariff:

Decrease in consumer surplus:

- $0.720 bn-$1.280 bn = -$0.460 bn

Increase in producer surplus:

- $0.320 bn-$0.080 bn = $0.240 bn

Government tax revenue:

- $0.160 bn

Deadweight losses

- $-0.080 bn - $0.080 bn = -$0.160 bn

Recall The Consequences of a Tariff (Say on Sugar)

Domestic consequences of tariff:

A $240m gain to a small group of domestic sugar producers at a $460m expense to consumers

Concentrated benefit, dispersed cost each consumer pays $0.04/lb more for sugar

Harm to foreigners: hurts exporters and consumers in other countries from lost trade

Sugar Tariff

Rent-Seeking

The Ugly of Monopoly: Rent-Seeking II

Think of an economic rent as a "prize," the payment a person receives for a good above its opportunity cost

Creating rents creates competition for the rents, causing people to invest resources in rent-seeking

The cost of the rent is not just the rent itself, but the resources invested in rent-seeking!

Government Intervention Creates Rents I

Political authorities intervene in markets in various ways that benefit some groups at the expense of everyone else

- subsidies to groups (often producers)

- regulation of industries

- tariffs, quotas, and special exemptions from these

- tax breaks and loopholes

- conferring monopoly and other privileges

See Mitchell (2013) in today's readings for examples

Government Intervention Creates Rents I

These interventions create economic rents for their beneficiaries by restricting competition

This is a transfer of wealth from consumers/taxpayers to politically-favored groups

The promise of earning a rent breeds competition over the rents (rent-seeking)

- investments of resources to lobby political officials

Rent-Seeking II

Gordon Tullock

1922-2014

"The rectangle to the left of the [Deadweight loss] triangle is the income transfer that a successful monopolist can extort from the customers. Surely we should expect that with a prize of this size dangling before our eyes, potential monopolists would be willing to invest large resources in the activity of monopolizing. ... Entrepreneurs should be willing to invest resources in attempts to form a monopoly until the marginal cost equals the properly discounted return," (p.231).

Tullock, Gordon, (1967), "The Welfare Cost of Tariffs, Monopolies, and Theft," Western Economic Journal 5(3): 224-232.

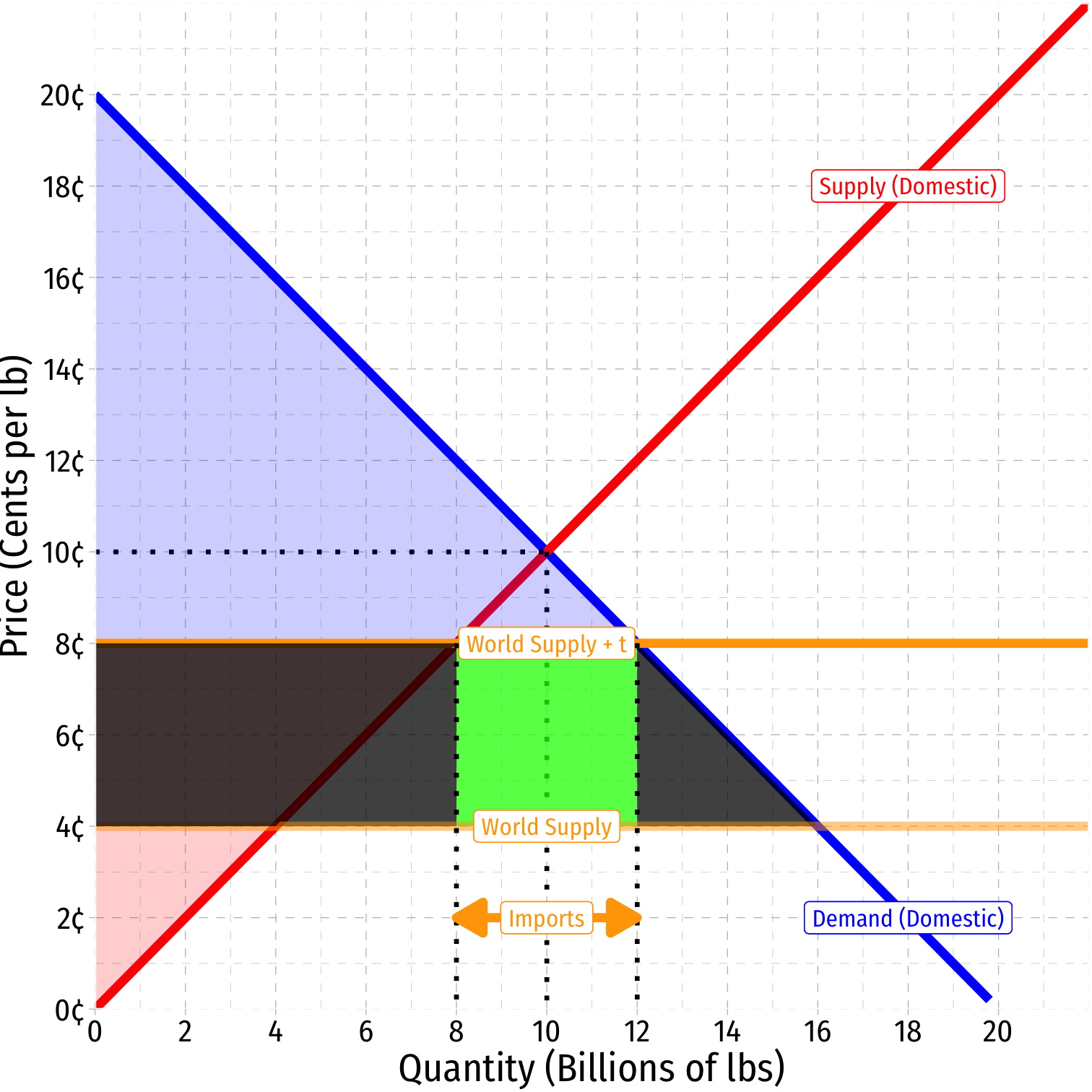

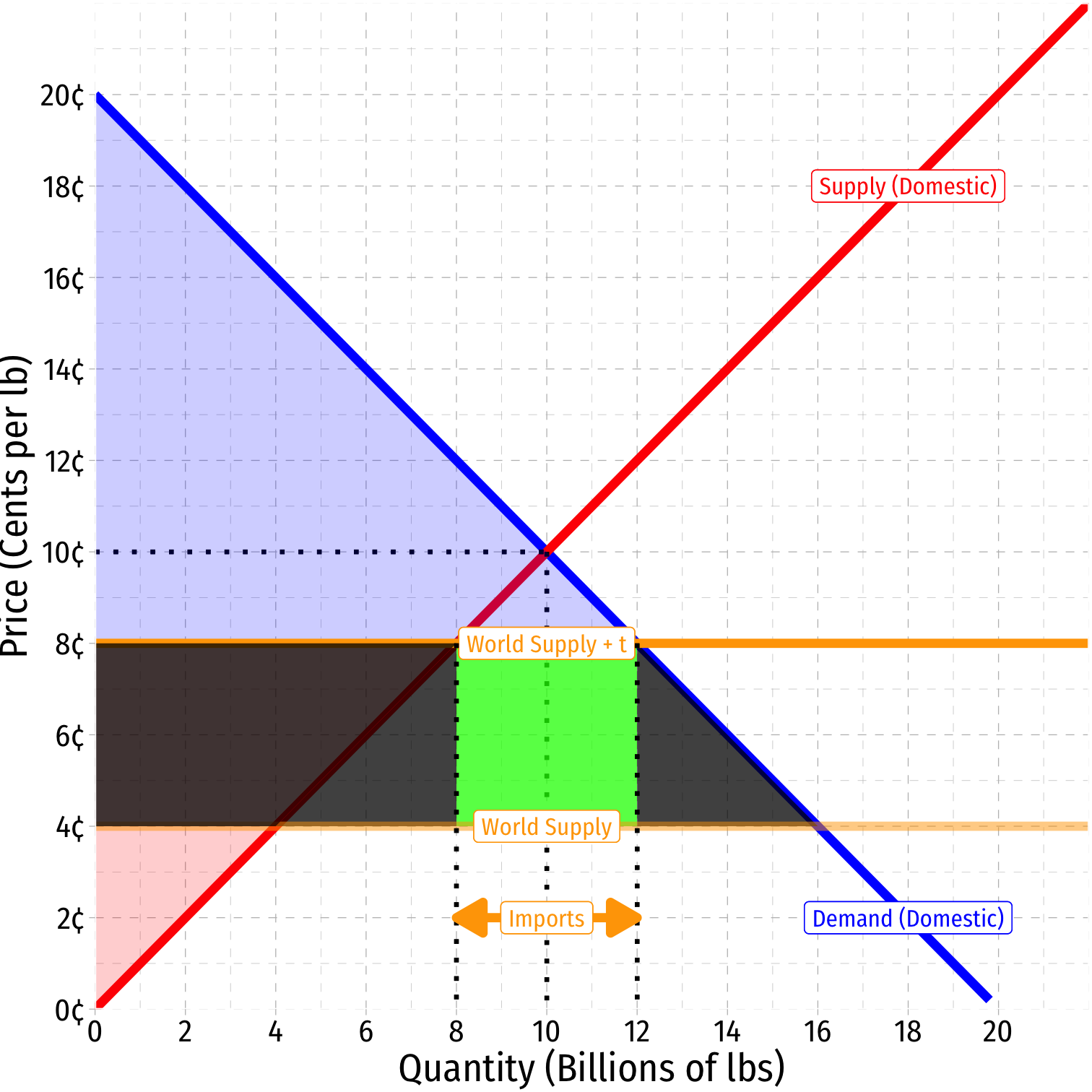

Rent-Seeking: Tariffs

- Normal effects of a tariff (↓ CS, ↑ PS, DWL, G)

Rent-Seeking: Tariffs

Normal effects of a tariff (↓ CS, ↑ PS, DWL, G)

The transfer of CS → PS is a “prize” (economic rent) to domestic producers

- Domestic producers are willing to expend resources to lobby the government to obtain this rent

Rent-Seeking: Tariffs

Normal effects of a tariff (↓ CS, ↑ PS, DWL, G)

The transfer of CS → PS is a “prize” (economic rent) to domestic producers

- Domestic producers are willing to expend resources to lobby the government to obtain this rent

The true social cost of the tariff is much larger than the 2 DWL triangles!

Who Gets Protection?

Is Trade Policy For Sale?

“The bigger contributions you accept, the more expectations some people have that they have a call on their government for something in return” — Senator Joseph Liebermann, 1997

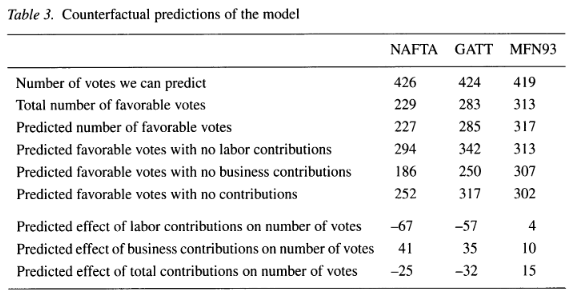

“Conventional wisdom suggests that interest groups are buying something when they contribute to a politician's campaign. mpaign. These interest groups must be giving money to influence either the outcome of the election or the policy decisions made by elected officials. Senator Lieberman's statement highlights the second possibility — that campaign contributions allow interest groups to affect policy outcome,” (p.80)

“This paper attempts to determine the importance of campaign contributions and other factors affecting voting behavior in the House of Representatives on three important trade-policy bills that came before the United States Congress in 1993-1994,” (p.80)

Is Trade Policy For Sale?

“Policies are determined by the interactions between elected officials, who are suppliers of particular public policies, and organized interest groups, who are demanders of such policies. Interest groups provide the campaign funds that public officials need to stress the merits of their candidacies to imperfectly informed voters. In exchange, politicians provide public policies that raise the economic rents earned by the interest groups. These rent-seeking activities are constrained by increased political opposition from individuals and firms whose welfare is reduced by the policy actions...In the end, government officials implement the policy that maximizes their political support,” (p.80)

Is Trade Policy For Sale?

“Two main trade models provide divergent predictions about which groups in the U.S. will support trade liberalization.

“In the Heckscher-Ohlin trade model, relatively scarce factors of production lose economically from international trade while relatively abundant factors gain...Since the United States is relatively scarce in less skilled labor, the model suggests that legislators will be more likely to oppose NAFTA, GATT and MFN for China the higher the proportion of less educated individuals and the lower the per-capita income in their districts. Because labor unions represent mainly blue-collar workers, a higher proportion of union members in a district also increases the likelihood the representative will oppose the trade bills.

“The [specific factors] trade model, on the other hand, assumes that the services of some productive factors are completely or partly industry-specific. A natural resource or particular type of physical capital may be suitable for use only in a single industry or a few industries, for example, and workers may acquire sector-specific skills. The implication is that individuals' attitudes toward trade liberalization depend on the industry in which they are employed rather than on their factor status,” (pp.80-81).

Baldwin, Robert E and Christopher S Magee, (2000) “Is Trade Policy for Sale? Congressional Voting on Recent Trade Bills,” Public Choice 105: 79—101

Is Trade Policy For Sale?

“We divide campaign contributions into those from PACs representing labor unions and from PACs representing business interests. The Heckscher-Ohlin model suggests that labor unions will oppose free trade while business groups will support it...labor and business contributions significantly affected legislators' decisions on both the NAFTA and GATT bills.”

Baldwin, Robert E and Christopher S Magee, (2000) “Is Trade Policy for Sale? Congressional Voting on Recent Trade Bills,” Public Choice 105: 79—101

Is Trade Policy For Sale?

“We estimate that labor contributions or access to legislators gained through these contributions resulted in 67 extra votes against NAFTA and 57 extra votes against the GATT Uruguay Round bill. Contributions from business groups resulted in 41 extra votes in favor of NAFTA and 35 extra votes for the GATT bill. This last result is particularly interesting because it suggests that NAFTA would have failed if business groups had made no contributions to repres- entatives. We estimate the price for labor groups to sway one vote against NAFTA and GATT to be about $352,000 and $313,000 respectively,” (p.99).

Baldwin, Robert E and Christopher S Magee, (2000) “Is Trade Policy for Sale? Congressional Voting on Recent Trade Bills,” Public Choice 105: 79—101

Trade Policy & Interest Groups: Politicians For Sale?

“What is distinctive in our approach is the role we ascribe to political contributions: we see the gifts made by interest groups not so much as investments in the outcomes of elections, but more as a means to influence government policy. In our view, the manner of campaign and party finance in many democratic nations creates powerful incentives for politicians to peddle their policy influence. Then the structure of trade protection is bound to reflect the outcome of a competition for political favors; this is the central theme in our story,” (p.848)

Grossman, Gene M and Elhanan Helpman, 1994, “Protection for Sale,” American Economic Review 84(4): 833-850.

Trade Policy & Interest Groups: Politicians For Sale?

“In our model, lobbies make implicit offers of political contributions as functions of the vector of trade policies (export and import taxes and subsidies) adopted by the government...We have derived an explicit formula for the structure of protection that emerges in such a setting. Our formula relates an industry's equilibrium protection to the state of its political organization, the ratio of domestic output in the industry to net [international] trade, and the elasticity of import demand or export supply,” (p.848).

Grossman, Gene M and Elhanan Helpman, 1994, “Protection for Sale,” American Economic Review 84(4): 833-850.

Who Gets Protected?

- Less efficient, declining industries tend to obtain protection

- Labor-intensive industries

- Low-skill industries

- Low-wage industries

- Industries with high/increasing competition from imports

- Industries that product consumer goods (as opposed to producer goods), especially where consumers are not organized (to oppose)

Who Gets Protected: Agriculture

1) Agriculture

- About 2 million farmers in the U.S. (1.5% of the civilian labor force), yet very politically powerful

- U.S. is largely a food exporter, so protection is not so much (import) tariffs but (export) subsidies

- European Union's Common Agricultural Policy export subsidies boost farm prices 2-3x the world price

- Japan's import substitution of rice: almost entirely bans imported rice, raising domestic prices to 5x the world price

Who Gets Protected: Clothing

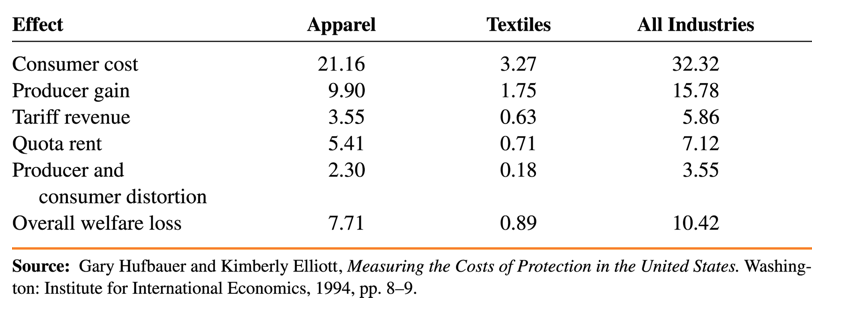

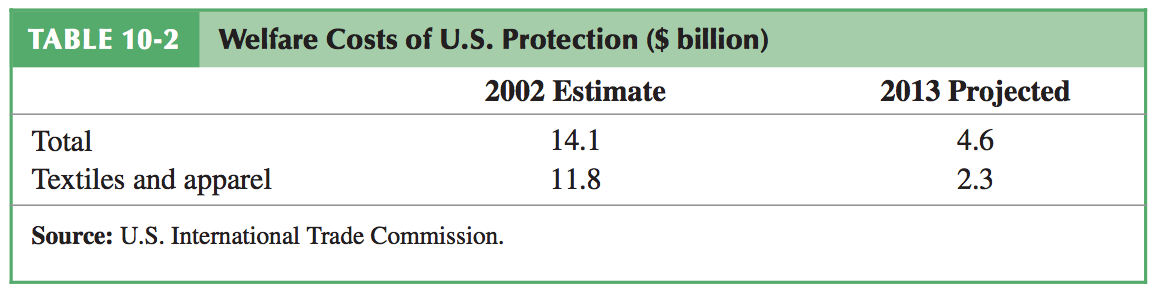

2) Clothing: textiles & apparel

- Until 2005: Multi-Fiber Arrangement (MFA) set export and import quotas for many countries

- Clothing is very labor-intensive

- H-O theory ⟹ we should import clothing

- High-wage countries (like U.S.) have comparative disadvantage vs. developing countries with comparative advantage

- U.S. clothing-manufacturers need protection to compete

Krugman, Paul, Maurice Obstfeld, and Mark Melitz, 2011, International Economics: Theory & Policy, 9th ed., p.234