1.11 — New Trade Theory

ECON 324 • International Trade • Spring 2023

Ryan Safner

Associate Professor of Economics

safner@hood.edu

ryansafner/tradeS23

tradeS23.classes.ryansafner.com

Trade Puzzles

Trade Puzzles

Ricardian comparative advantage

Trade Puzzles

Hecksher-Ohlin factor endowments

Upending the Classic Paradigm

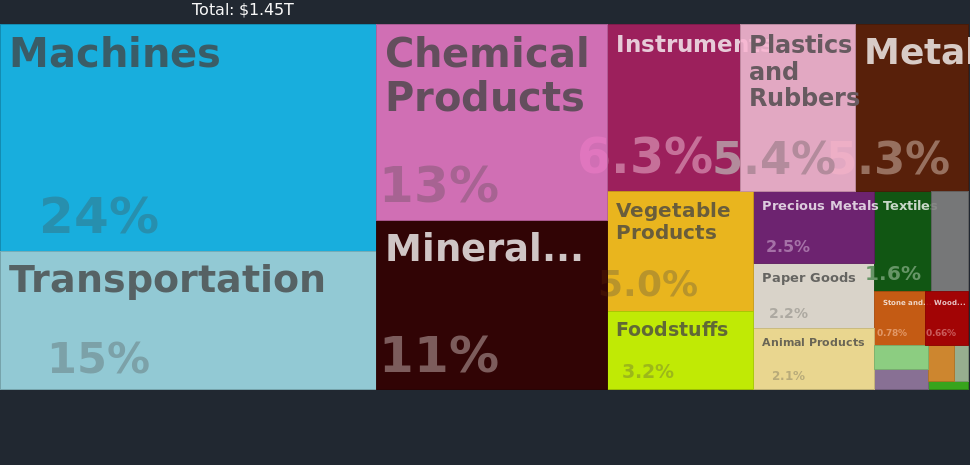

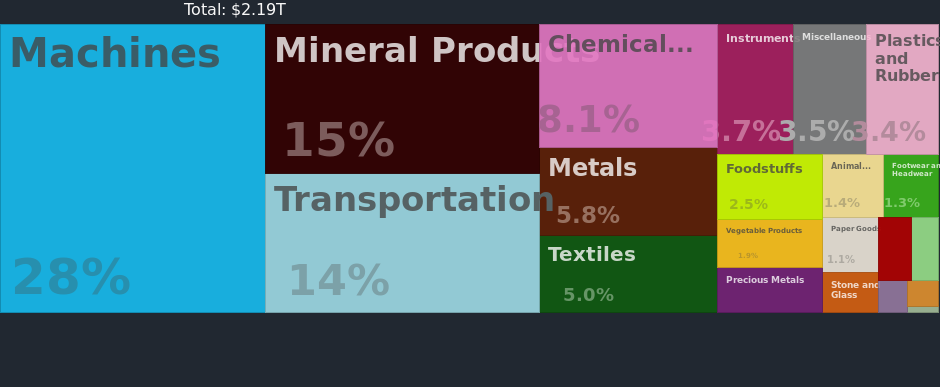

U.S. exports to Japan

Japan exports to U.S.

???

Intra-Industry Trade

- Intra-industry trade: share of international trade (exports + imports) that takes place within the same industry (across countries) rather than across industries

Intra-Industry Trade

Intra-industry trade: share of international trade (exports + imports) that takes place within the same industry (across countries) rather than across industries

Measured by the Grubel-Lloyd Index (GLI):

GLI=1−|Xi−Mi|Xi+Mi

where X is exports, M is imports, for industry i

Grubel-Lloyd Index

GLI=1−|Xi−Mi|Xi+Mi

Example: suppose a country exports good i but does not import good i:

GLI=1−1=0

- No intra-industry trade; only inter-industry trade

Grubel-Lloyd Index

GLI=1−|Xi−Mi|Xi+Mi

Example: same for a good a country imports but does not export:

GLI=1−1=0

- No intra-industry trade; only inter-industry trade

Grubel-Lloyd Index

GLI=1−|Xi−Mi|Xi+Mi

Example: what if a country’s exports of i≈ its imports of i?

GLI=1−0Xi+Mi=1

- Only intra-industry trade, no inter-industry trade

Grubel-Lloyd Index

GLI=1−|Xi−Mi|Xi+Mi

- GLI mesaures how closely exports & imports are matched within an industry

Grubel-Lloyd Index: Example I

GLI=1−|Xi−Mi|Xi+Mi

Example: In 2010, the U.S. exported $170 million and imported $1.9 billion worth of raw sugar cane.

GLI=1−|0.170−1.900|0.170+1.900=0.164

- Little intra-industry trade

Grubel-Lloyd Index: Example II

GLI=1−|Xi−Mi|Xi+Mi

Example: In 2010, the U.S. exported $1 billion and imported $1.2 billion worth of aircraft.

GLI=1−|1.000−1.200|1.000+1.200=0.909

- Mostly intra-industry trade

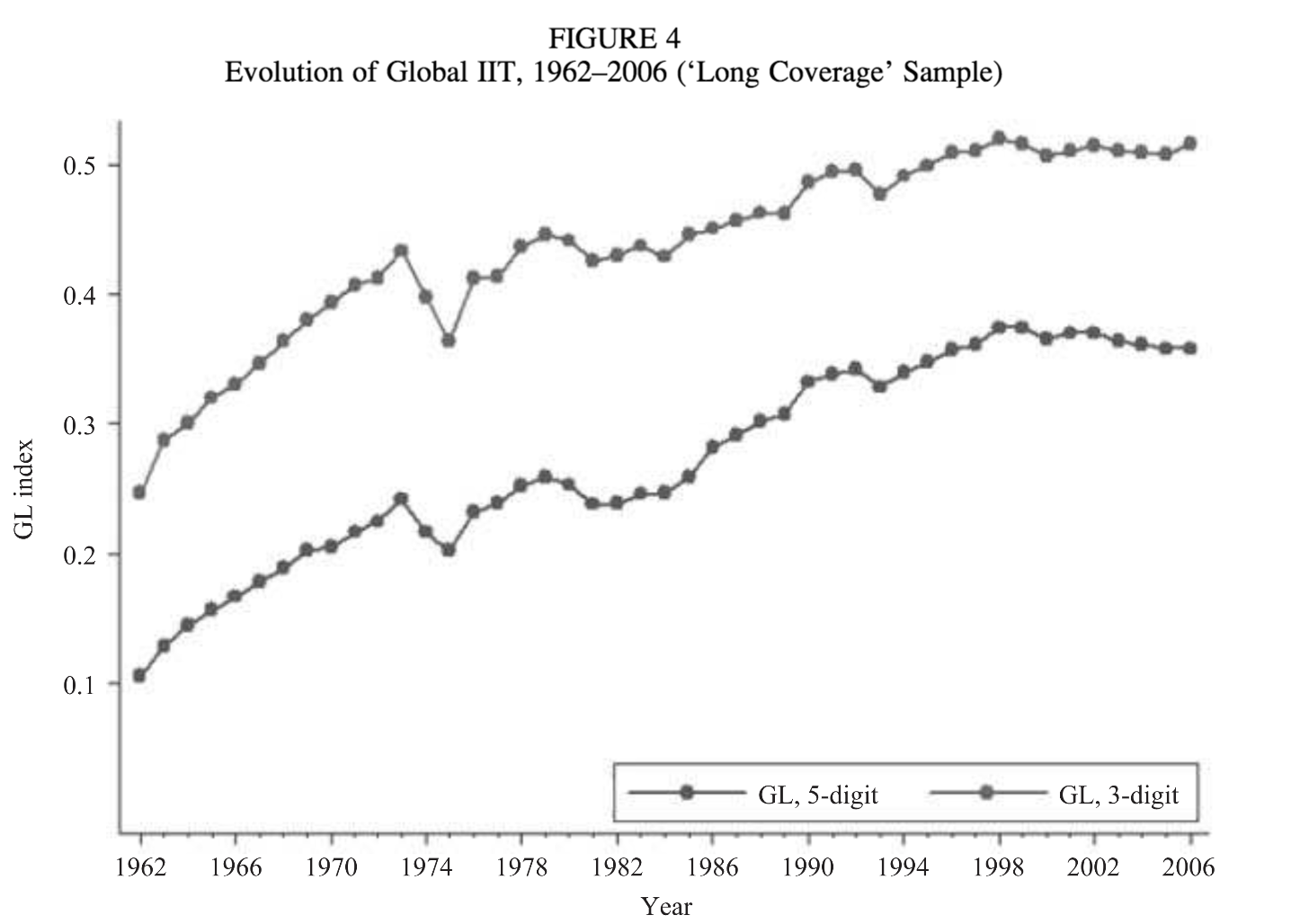

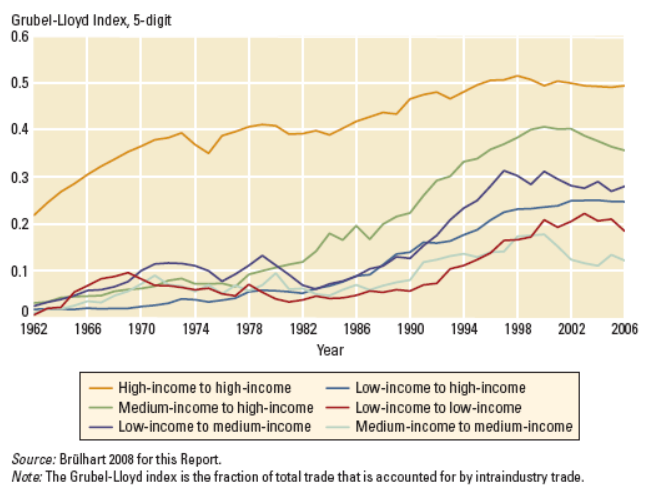

The Dilemma of Similar Trade

Brulhart, Marius, 2009, “An Account of Global Intra-industry Trade, 1962-2006,” The World Economy 32(2):401-459

The Dilemma of Similar Trade

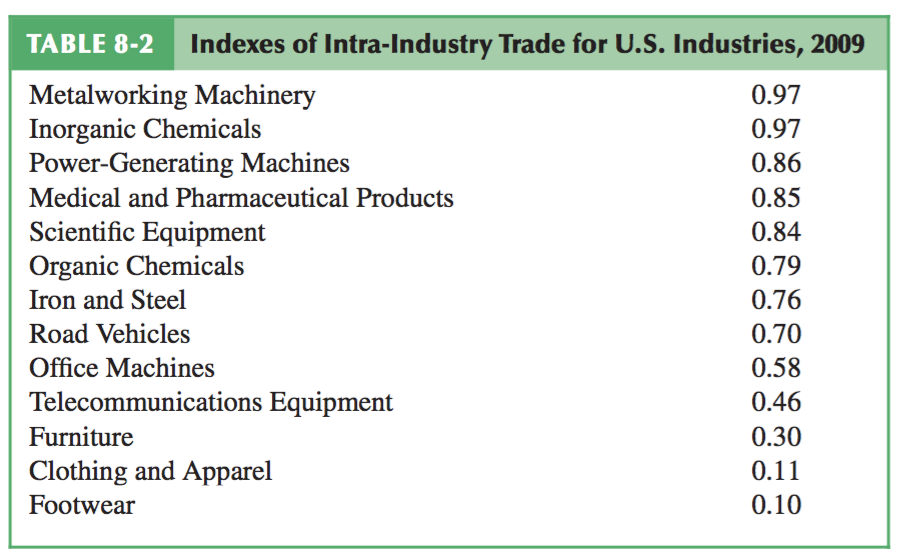

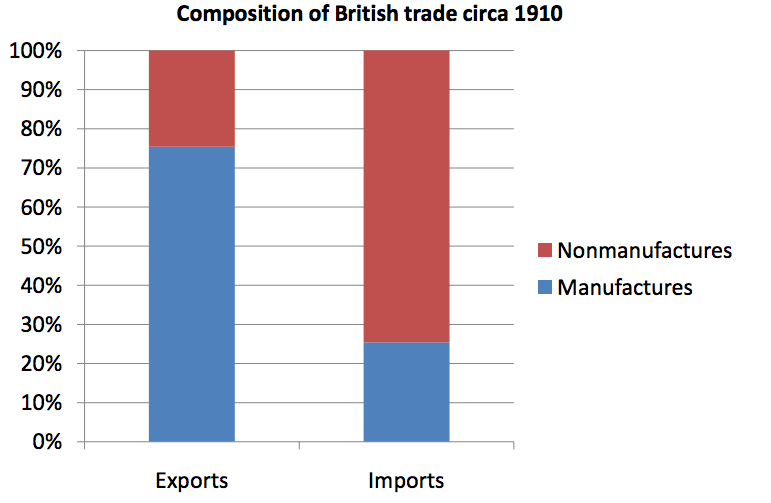

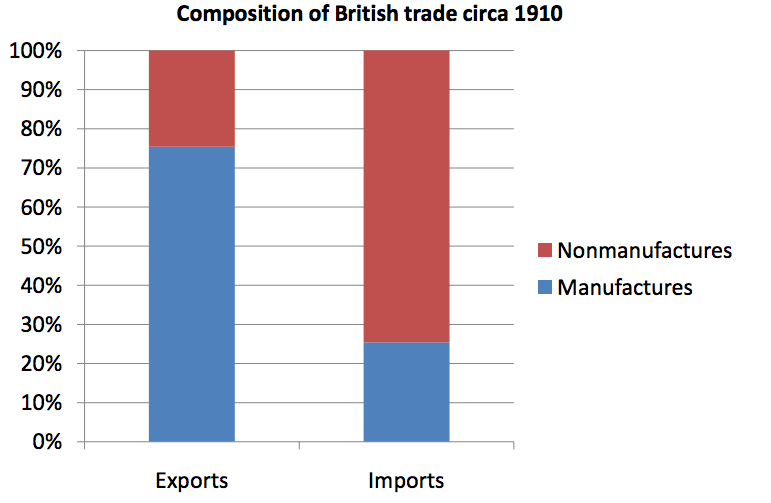

Krugman, Paul, Maurice Obstfeld, and Mark Melitz, 2011, International Economics: Theory & Policy, 9th ed., p.169

The Dilemma of Similar Trade

Krugman, Paul, Maurice Obstfeld, and Mark Melitz, 2011, International Economics: Theory & Policy, 9th ed., p.169

The Dilemma of Similar Trade

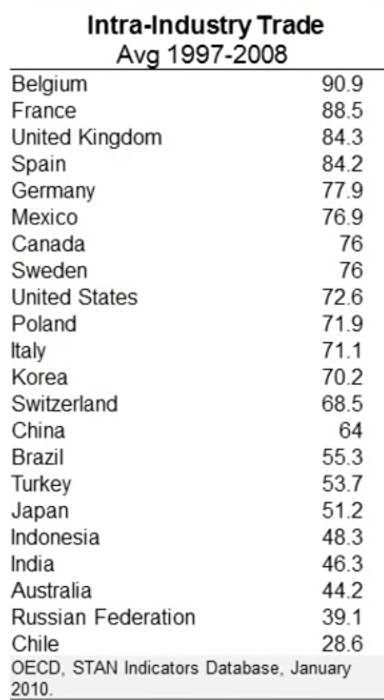

Total share of IIT by country (out of 100%): sum over all industries, weighing each industry by its share of total trade

Krugman, Paul, 2008, “The Increasing Returns Revolution in Trade and Geography,” Nobel Prize Lecture

The Dilemma of Similar Trade

The Dilemma of Similar Trade

Krugman, Paul, 2008, “The Increasing Returns Revolution in Trade and Geography,” Nobel Prize Lecture, p. 336-7

The Dilemma of Similar Trade

Krugman, Paul, 2008, “The Increasing Returns Revolution in Trade and Geography,” Nobel Prize Lecture, p.337

Who We Trade With (Exports) Has Changed

The Gravity Model of Trade

The Gravity Model of Trade

One way to estimate the volume of trade flows is with a gravity model of trade

Almost identically analogous to Newton’s model of gravitational attraction

F1,2=Gm1m2r2

The Gravity Model of Trade

Tradei,j=AMiMj(Di,j)n

- Volume of trade estimated between country i and country j

A: a universal constant

M: size of a country's economy (often GDP)

D: distance between country i and country j

- Power of distance: distance becomes a hinderance to trade at an increasing rate

- "Distance" need not be just length (e.g. miles, km), but relative to alternatives

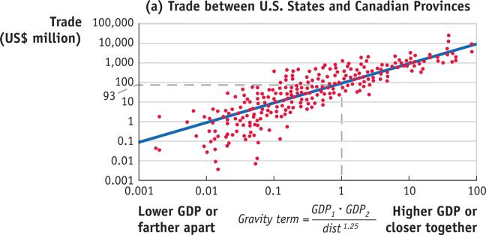

Gravity

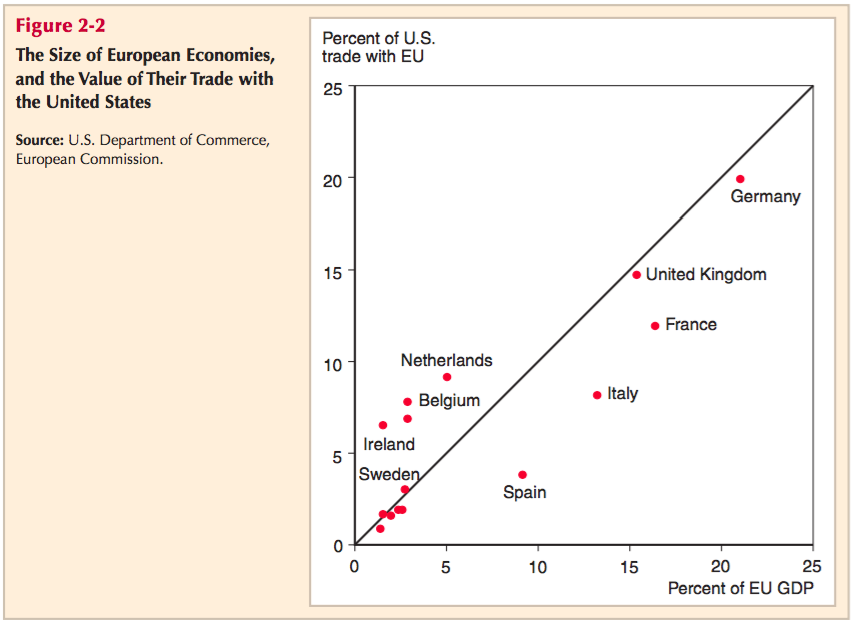

Krugman, Paul, Maurice Obstfeld, and Mark Melitz, 2011, International Economics: Theory & Policy, 9th ed., p.12

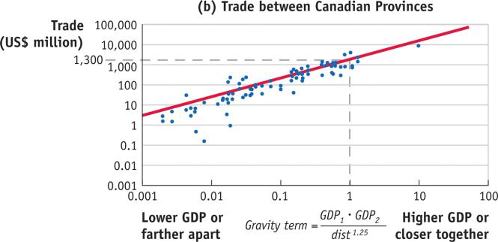

Gravity

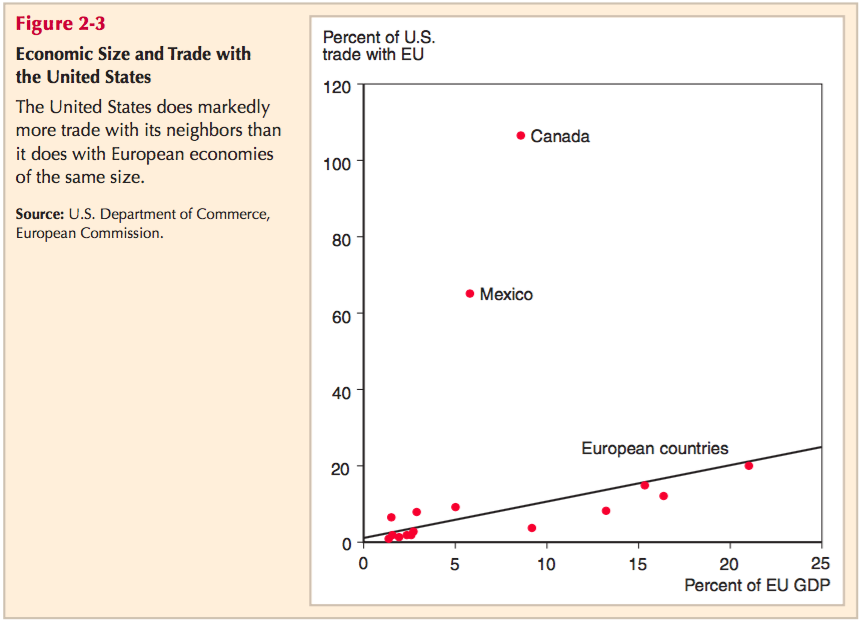

Krugman, Paul, Maurice Obstfeld, and Mark Melitz, 2011, International Economics: Theory & Policy, 9th ed., p.14

Gravity: Distance Matters

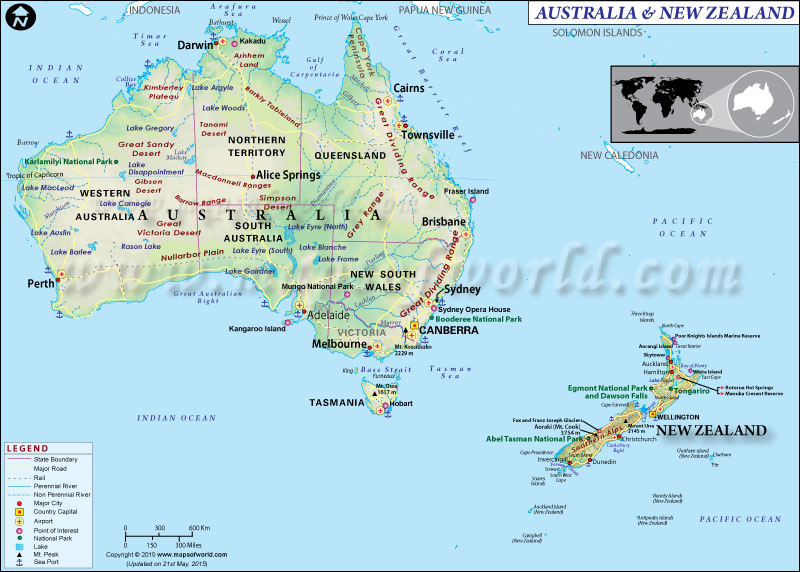

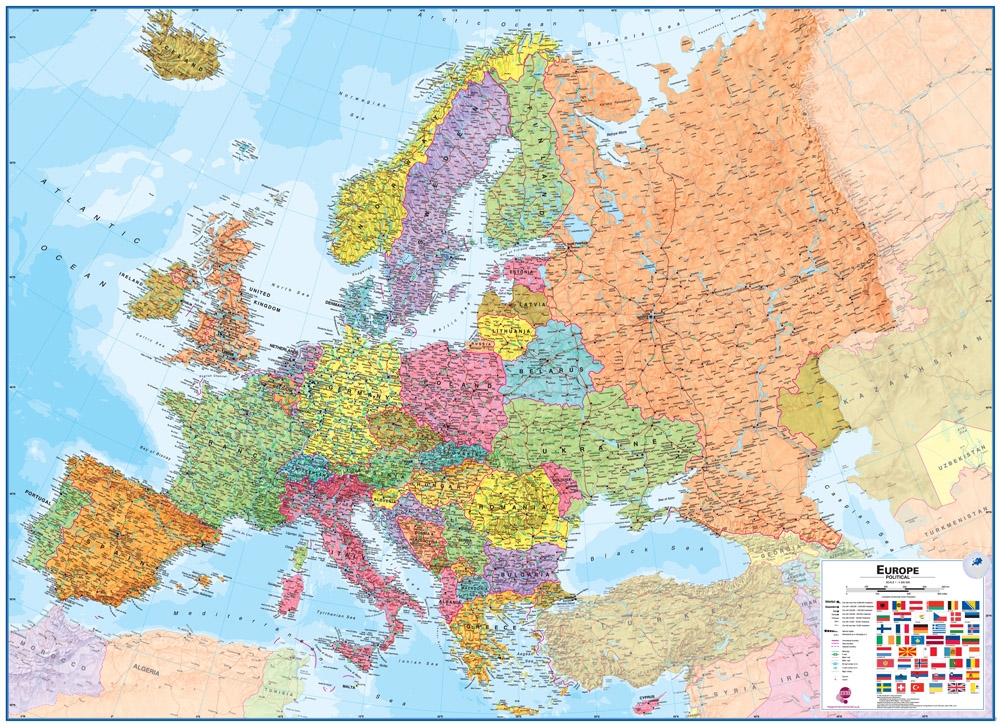

Consider trade between Australia & New Zealand and between Austria & Portugal

Both pairs have roughly same distance apart and roughly same GDPs

Trade between Australia and New Zealand is 9x higher than trade between Austria & Portugal!

Fewer alternatives in isolated Pacific Ocean relative to European countries with many trading partners

Gravity: Size & Distance Matters!

Feenstra and Taylor (2017)

Gravity: Size & Distance Matters!

Feenstra and Taylor (2017)

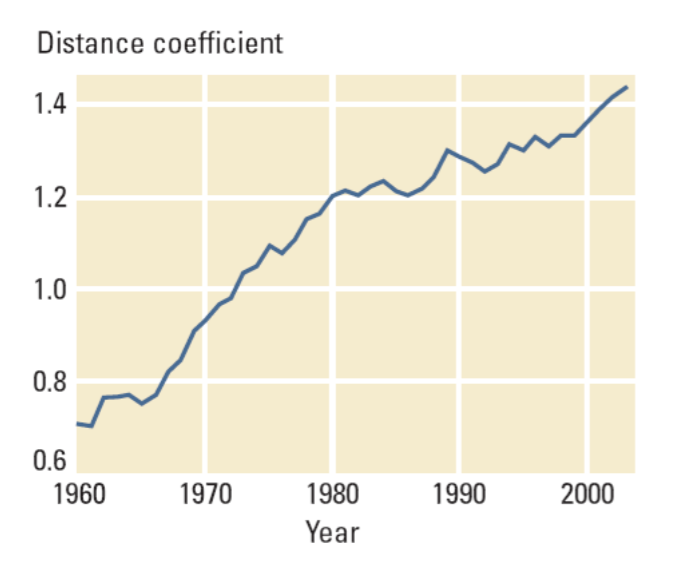

Gravity: Apparently Distance Matters More Now!

Tradei,j=AMiMj(Di,j)2

Trade is becoming more sensitive to distance over time!

Krugman, Paul, 2008, “The Increasing Returns Revolution in Trade and Geography,” Nobel Prize Lecture

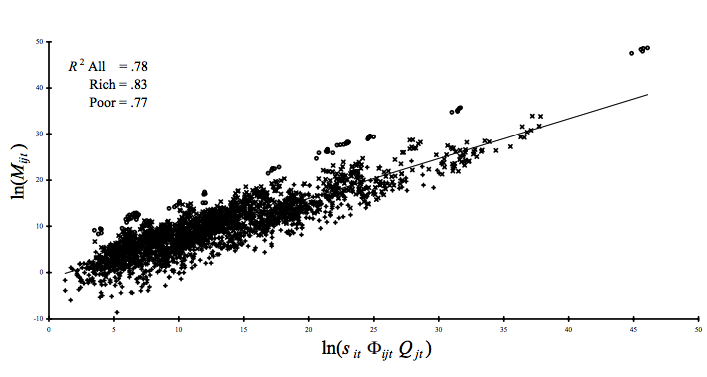

Gravity Always Wins

- "The gravity equation is one of the best fitting and most established empirical relationships in all of Trade."

Lai, Huiwen and Daniel Treffler, 2002, “The Gains from Trade with Monopolistic Competition: Specification, Estimation, and Mis-Specification”, NBER Working Paper 9169

Gravity

- Implications of Gravity Models:

1) Larger countries trade more with larger countries

2) Closer countries trade more than distant countries

Gravity vs. H-O Theory

Is gravity consistent with H-O theory?

- If trade drops off with distance, would require very strongly differentiated products to get trade off the ground

It used to be that most international trade was between countries very far apart for different things

- e.g. Britain imported wheat from Argentina, mutton from New Zealand

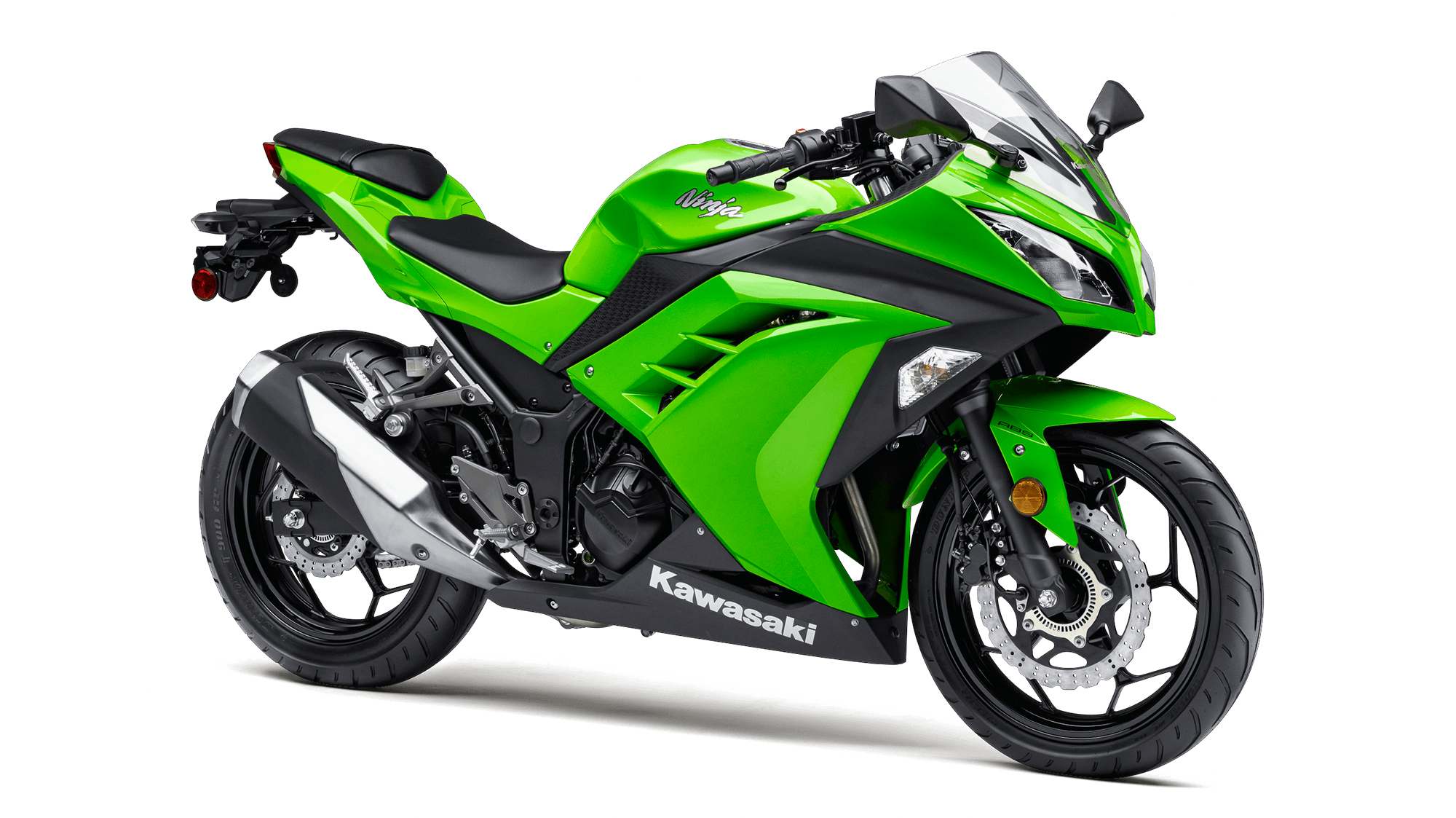

Now it seems to be that trade is dominated by very close countries trading very similar goods!

- Britain now both exports and imports airplanes to/from France and Germany

New Trade Theory

A New Paradigm in International Trade

In a Neoclassical world, only differences in relative autarky prices cause international trade via specialization by comparative advantage

- Ricardian differences in labor productivity

- Hecksher-Ohlin differences in factor endowments

Suggests that:

- "Different" countries should trade more

- "Different" countries should specialize in "different" goods

- Countries gain more from trading with more-distant countries

A New Paradigm in International Trade

The real world (particularly last 50 years) shows:

The bulk of international trade is between similar countries

These countries tend to trade similar goods

Countries are more likely than ever before to trade more with less-distant countries

New Trade Theory

Explanations for similar trade and a "new paradigm" of trade are collectively called New Trade Theory (NTT)

Primarily rests upon the idea of increasing returns to scale (IRS) or economies of scale (EOS) as an alternative rationale for international trade

- Countries can specialize in something, even if they have no ex ante comparative advantage

- Large output creates a comparative advantage ex post due to lower costs than other countries

New Trade Theory

Division of labor strikes back!

Importance is still specialization, just not labor productivity, factor content, etc.

Economies of Scale

Economies of scale come in two flavors:

Internal economies: firm-level features that improve a firm's productivity, often leading to market power for that firm

- e.g. firm produces more and lowers its average costs

External economies: industry-wide features that spill over to the productivity all firms in the industry

- e.g. more firms producing more lowers all firms' average costs

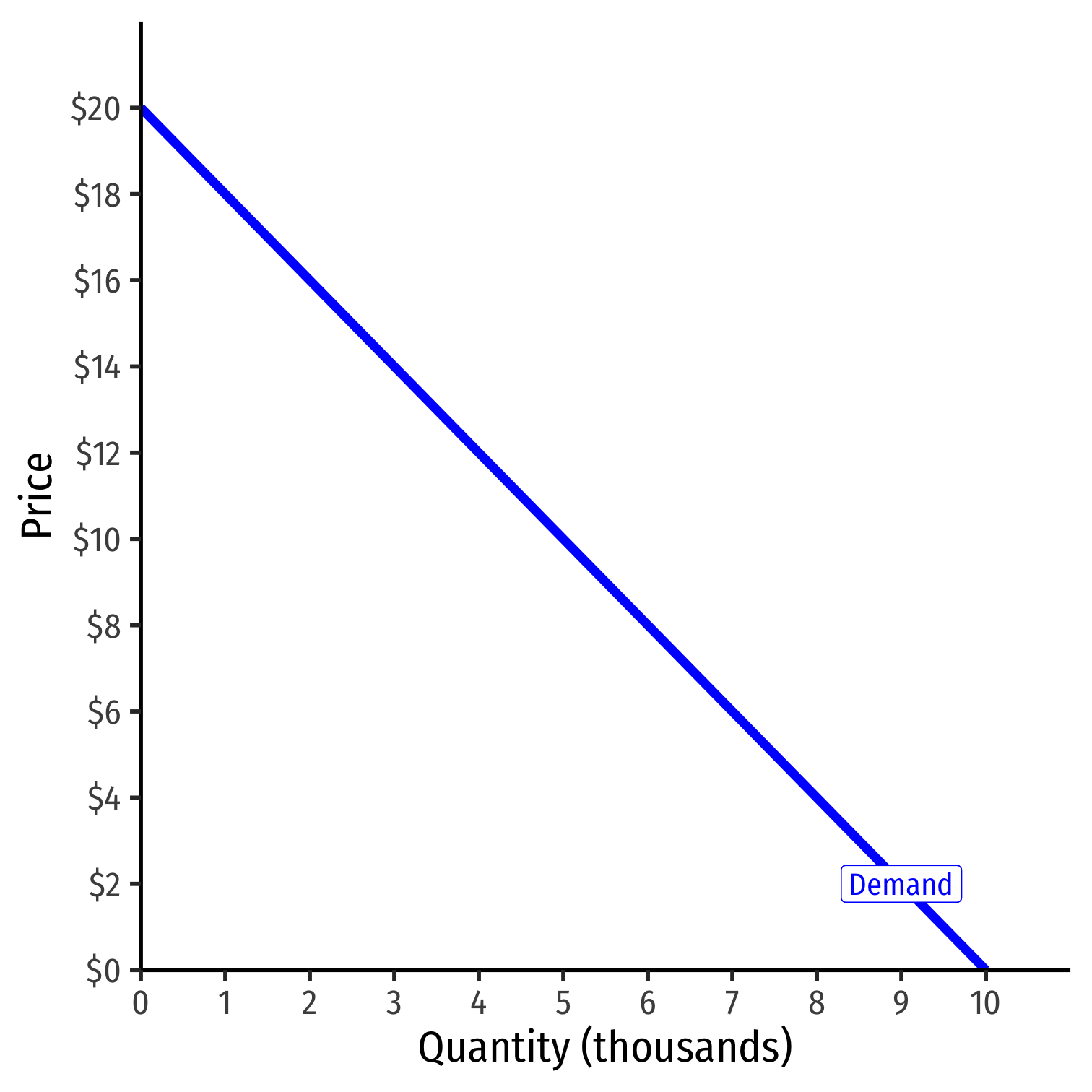

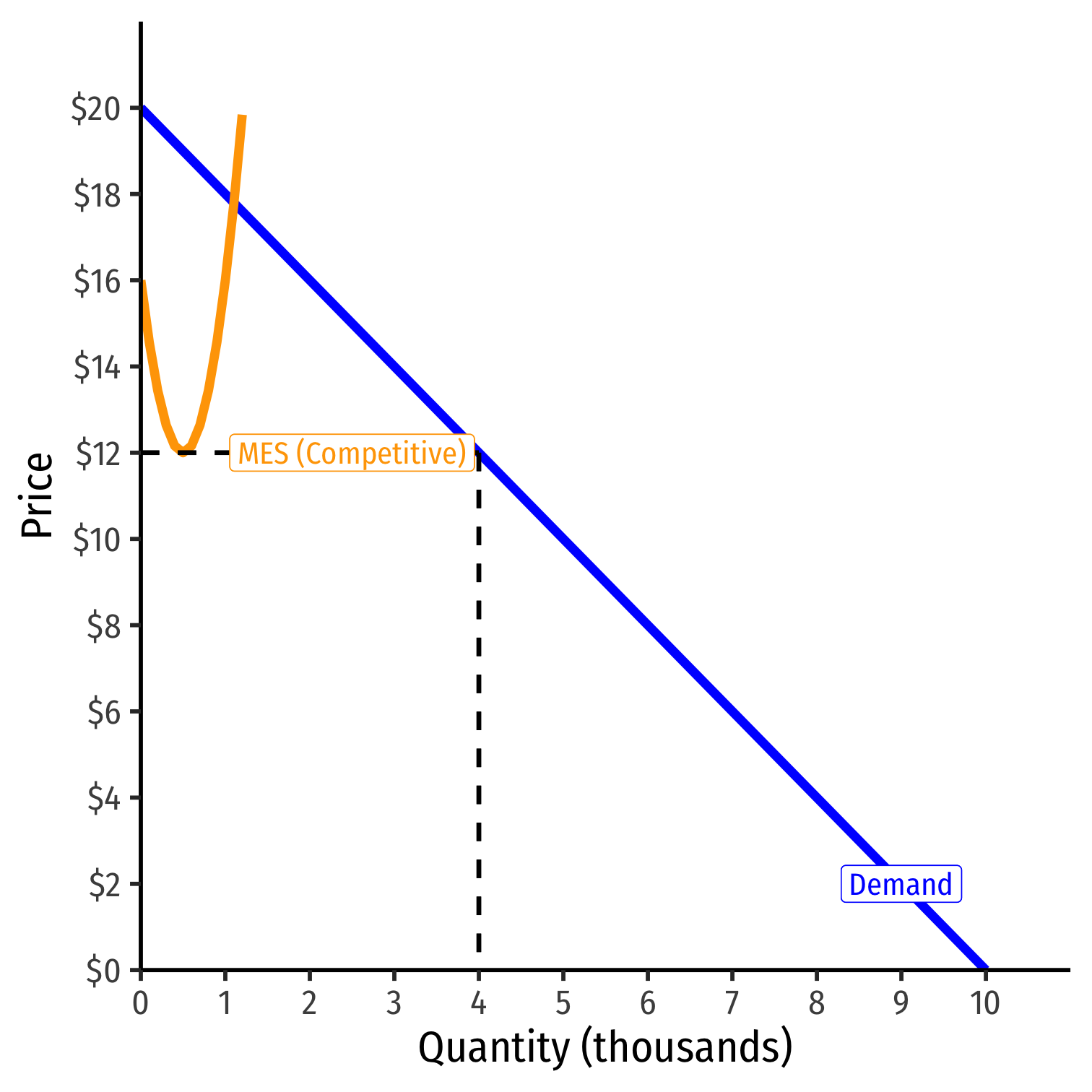

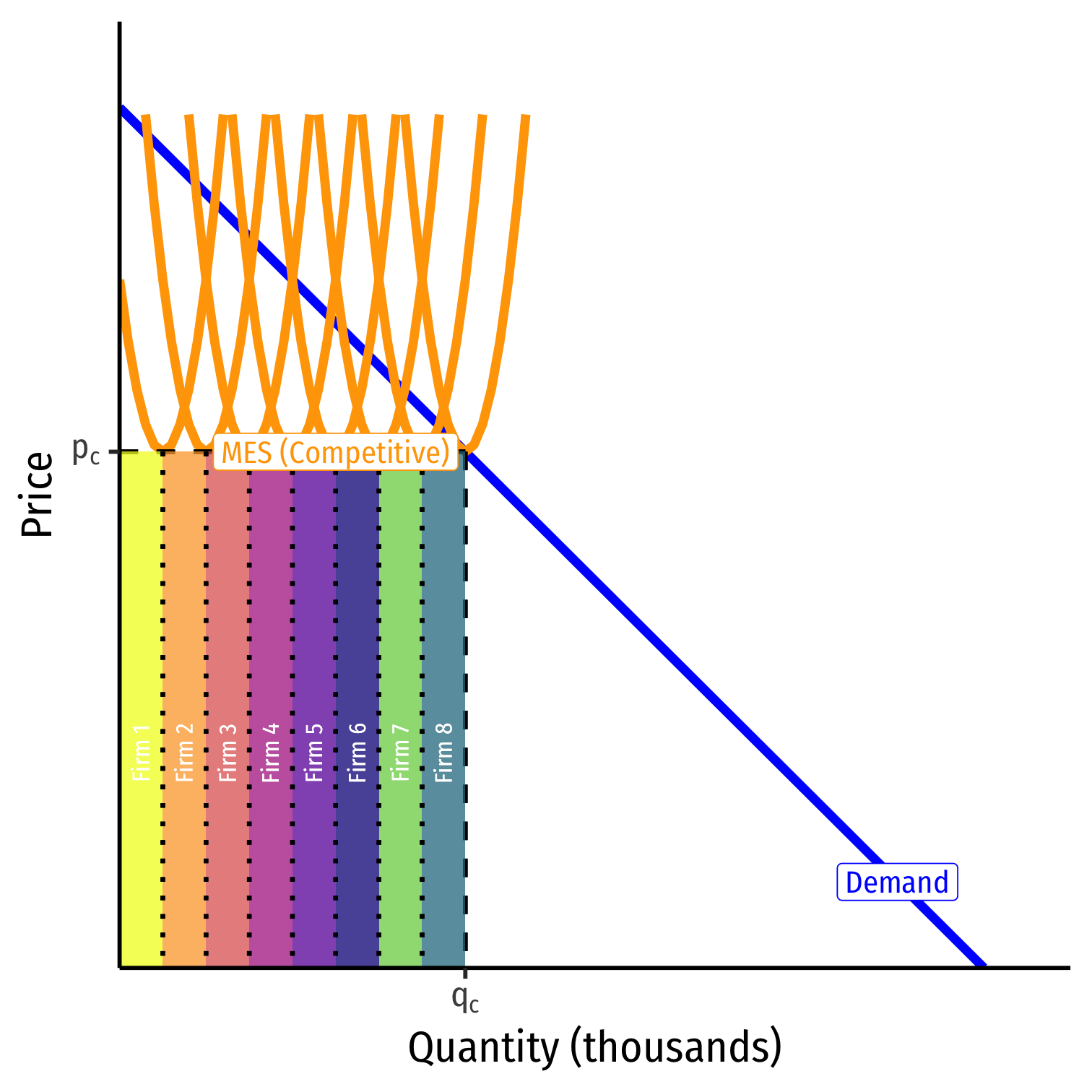

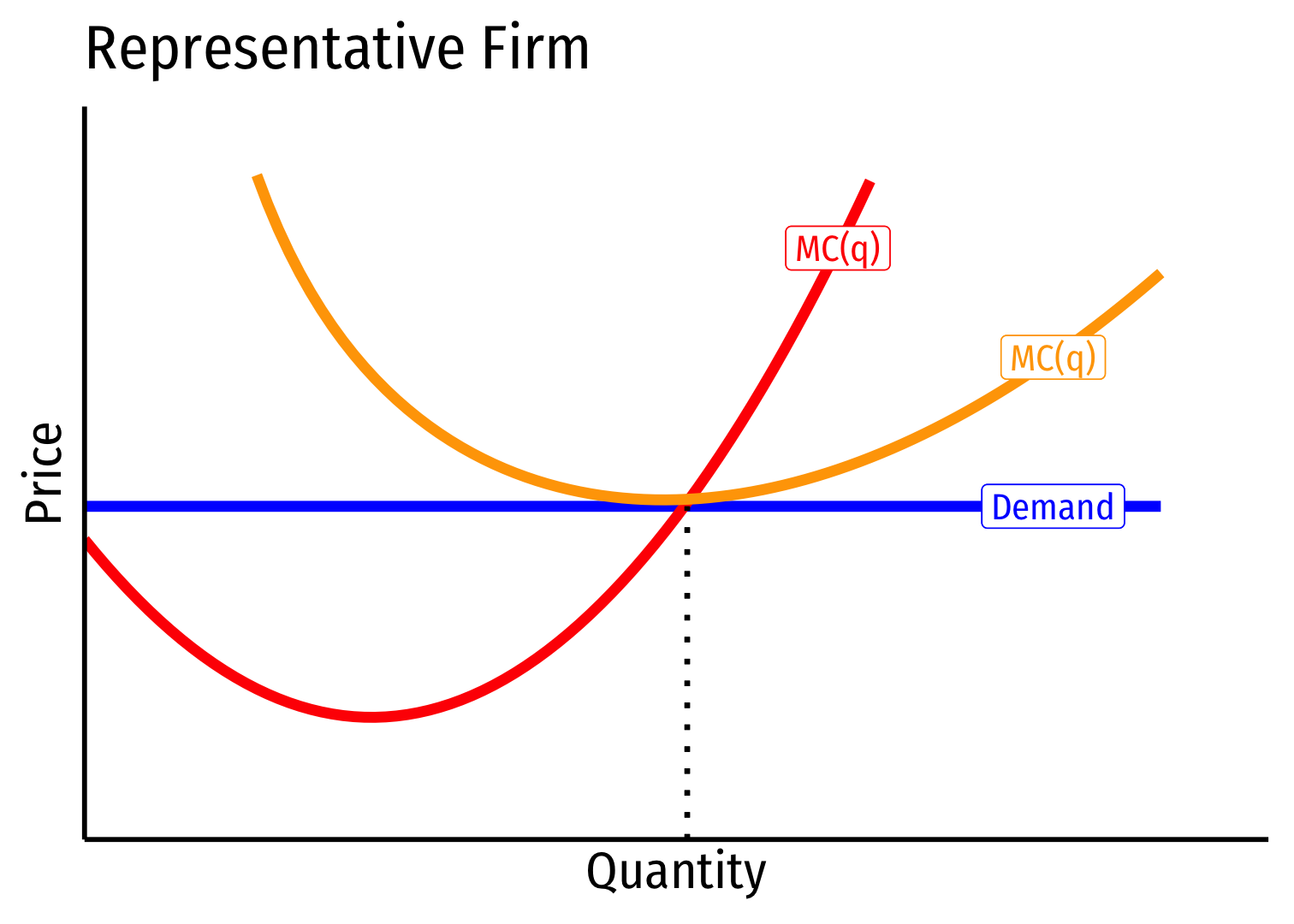

Internal Economies of Scale

Internal Economies of Scale I

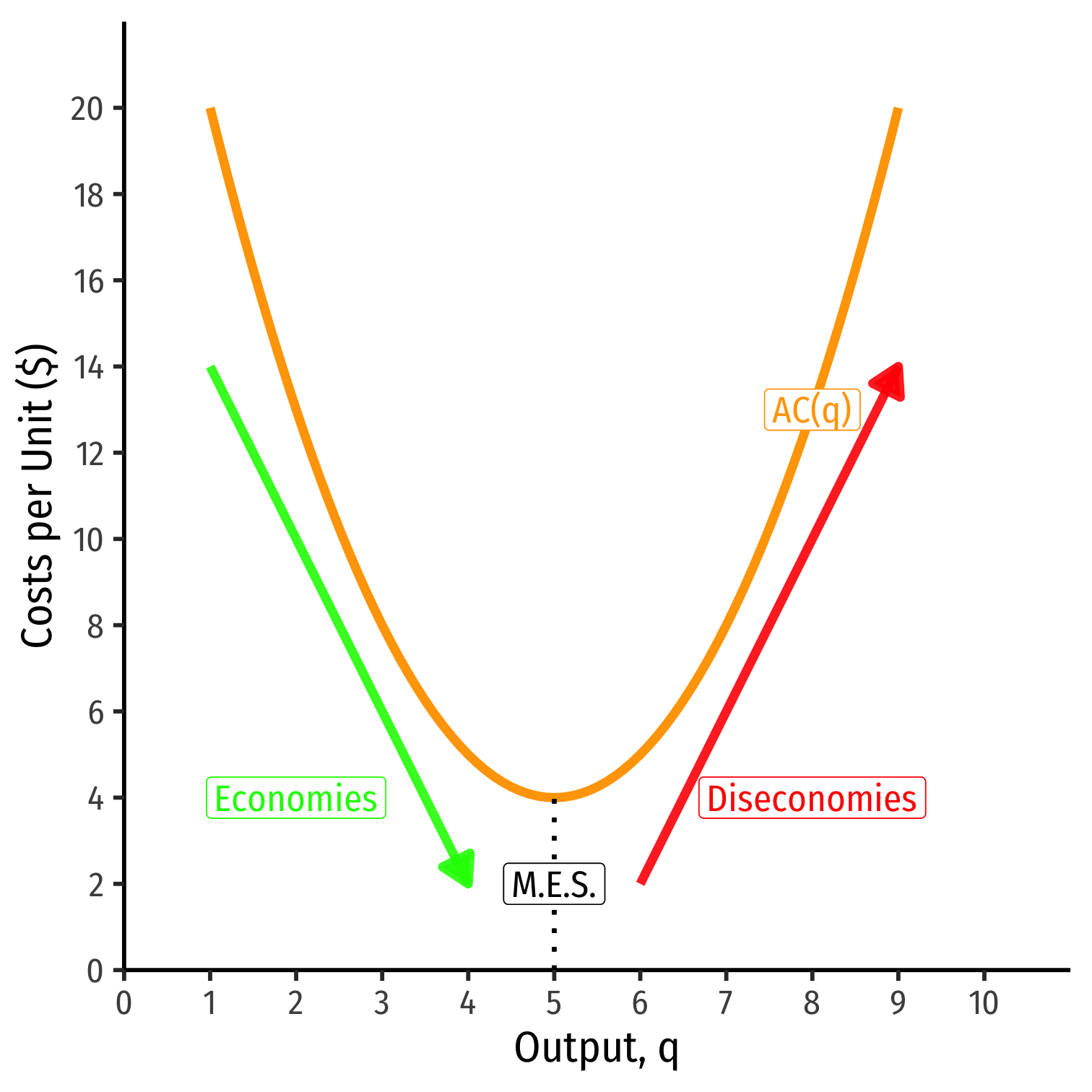

Recall: economies of scale: as ↑q, ↓AC(q)

Minimum Efficient Scale (MES): q with the lowest AC(q)

Internal Economies of Scale I

Recall: economies of scale: as ↑q, ↓AC(q)

Minimum Efficient Scale (MES): q with the lowest AC(q)

If MES is small relative to market demand...

- AC hits Market demand during diseconomies of scale...

Internal Economies of Scale

Minimum Efficient Scale: q with the lowest AC(q)

Economies of Scale: ↑q, ↓AC(q)

Diseconomies of Scale: ↑q, ↑AC(q)

Internal Economies of Scale I

- If MES is small relative to market demand...

- AC hits Market demand during diseconomies of scale...

- ...can fit more identical firms into the industry!

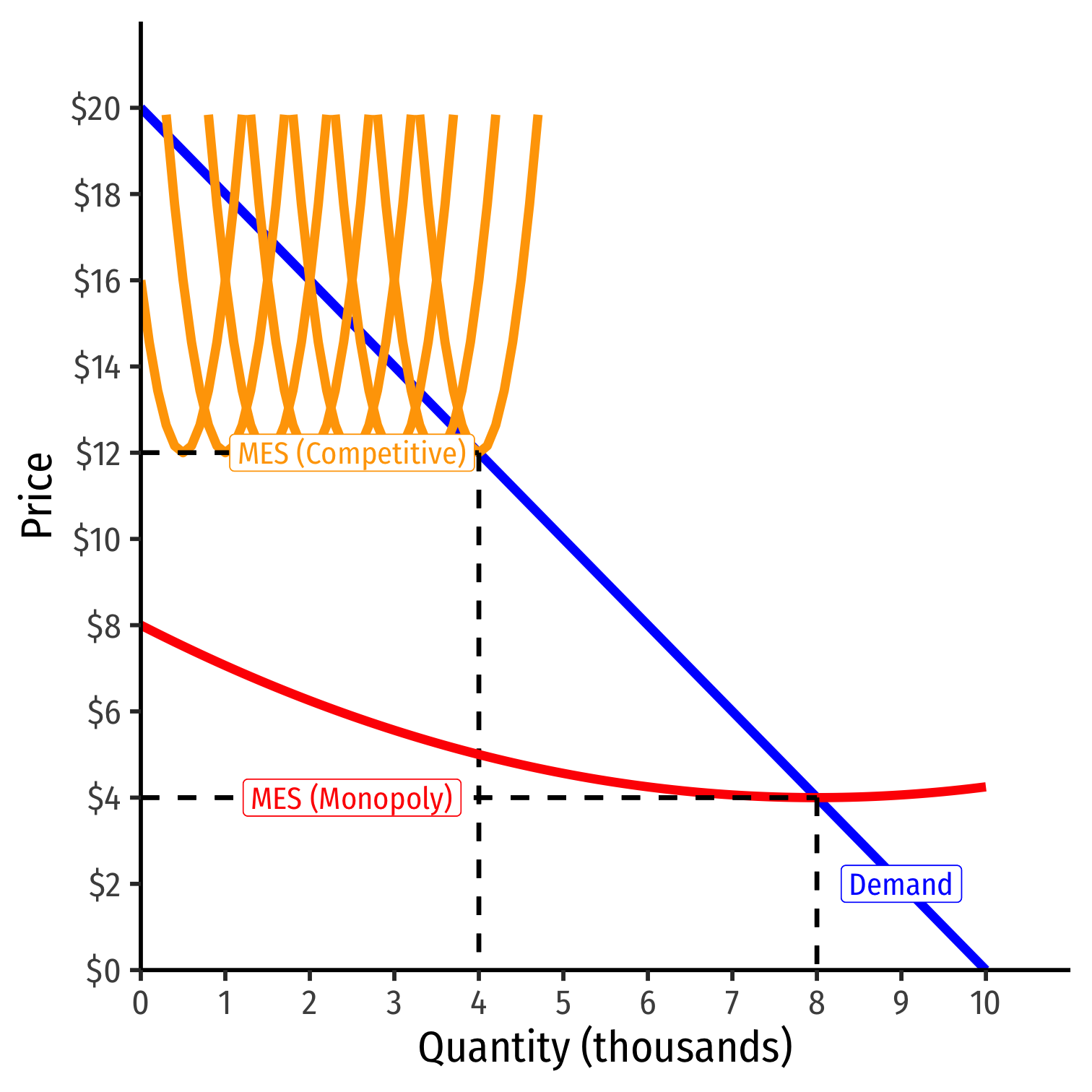

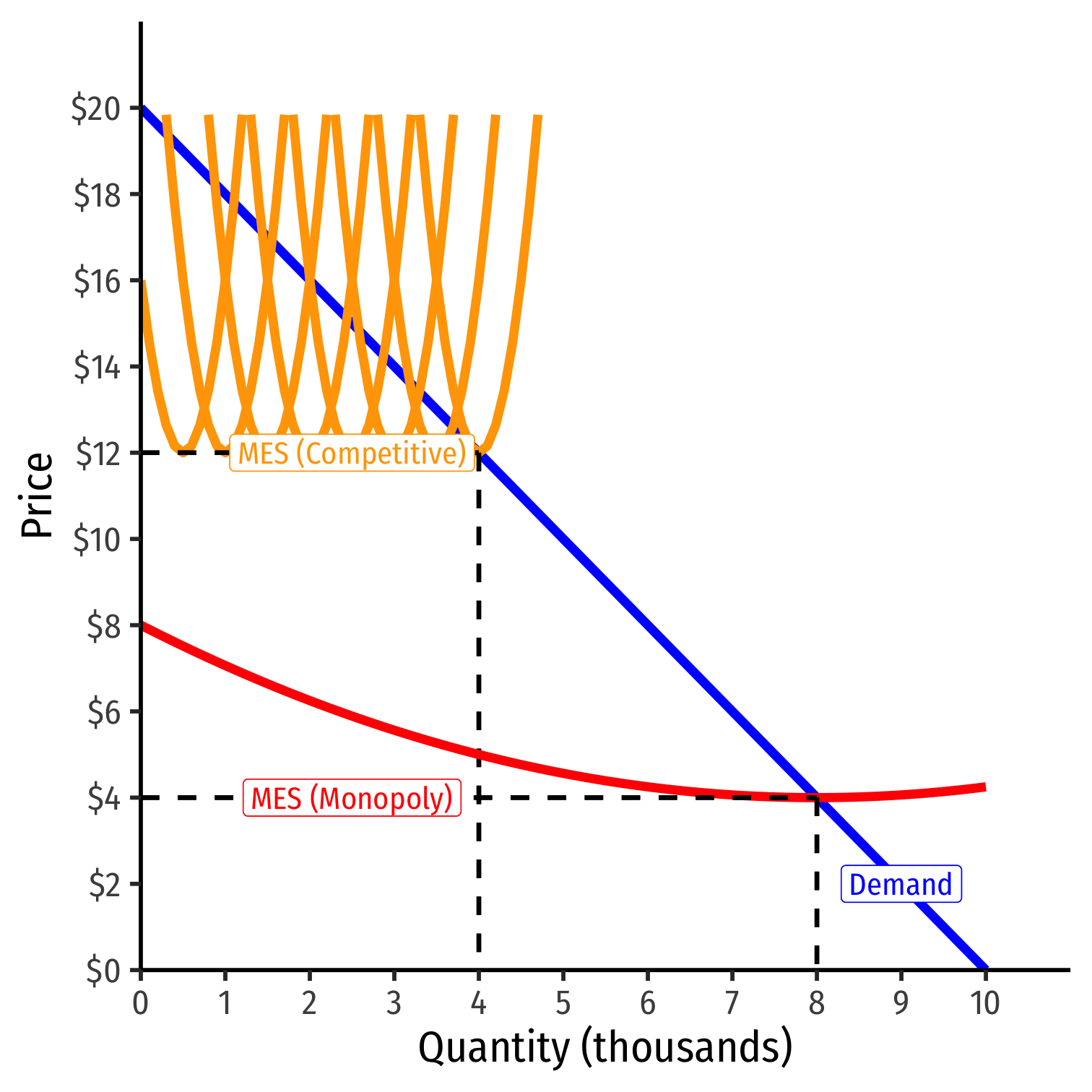

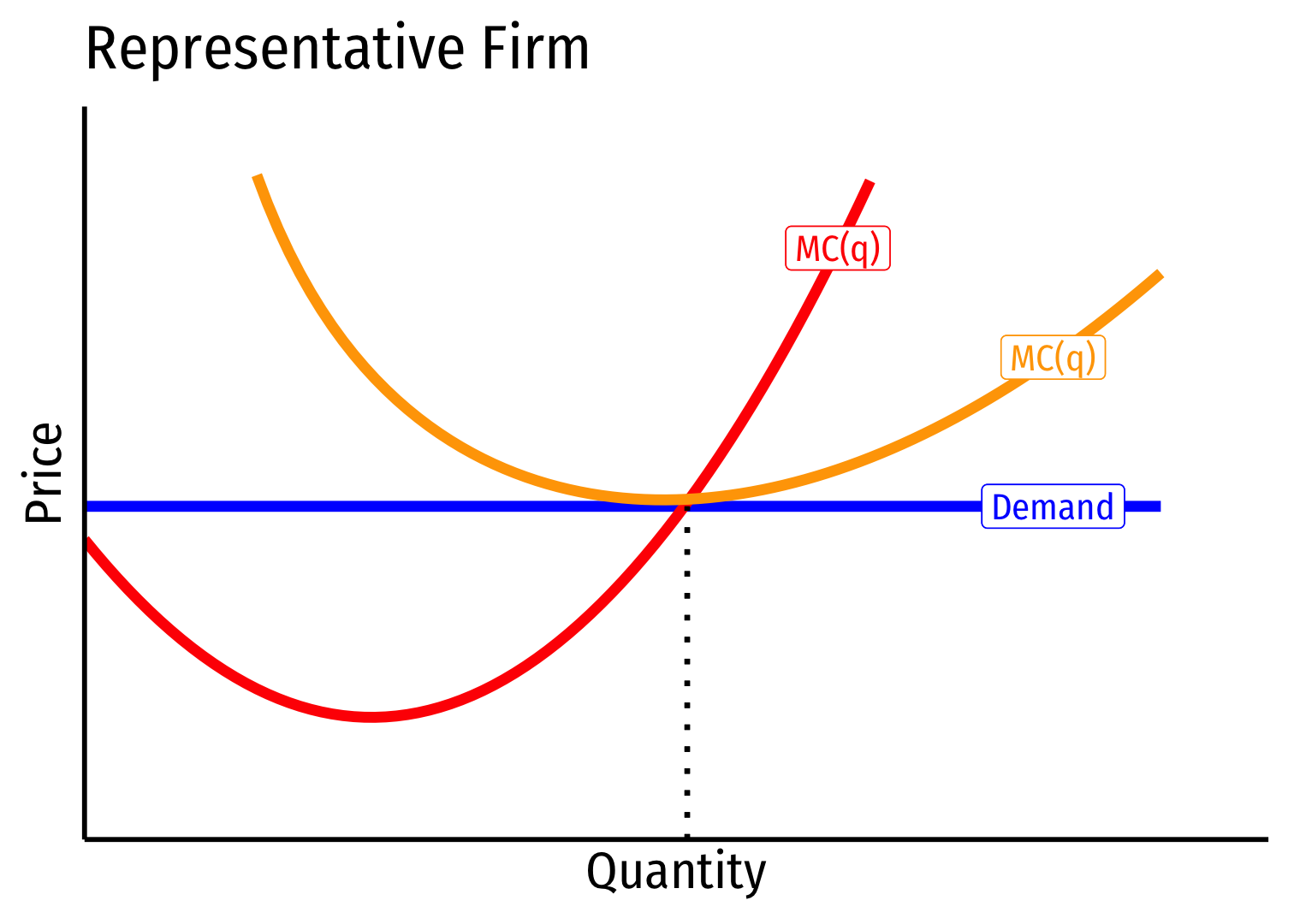

Internal Economies of Scale I

- If MES is large relative to market demand...

- AC hits Market demand during economies of scale...

- likely to be a single firm in the industry!

Internal Economies of Scale I

If MES is large relative to market demand...

- AC hits Market demand during economies of scale...

- likely to be a single firm in the industry!

A natural monopoly that can produce higher q∗ and lower p∗ than a competitive industry!

Internal Economies of Scale II

Example: Imagine a single isolated condo complex with 1,000 units far from any other buildings or telco infrastructure

- Fixed costs: laying cable to the complex is $100,000

- Marginal costs: connecting each unit: $0

Internal Economies of Scale II

- Suppose 10 providers split the complex, each laying down their own cables, and each serving 100 units:

Average cost=$100,000100=$1,000/subscriber

Internal Economies of Scale II

- Suppose 1 provider serves the complex serving all 1,000 units:

Average cost=$100,0001000=$100/subscriber

External Economies of Scale

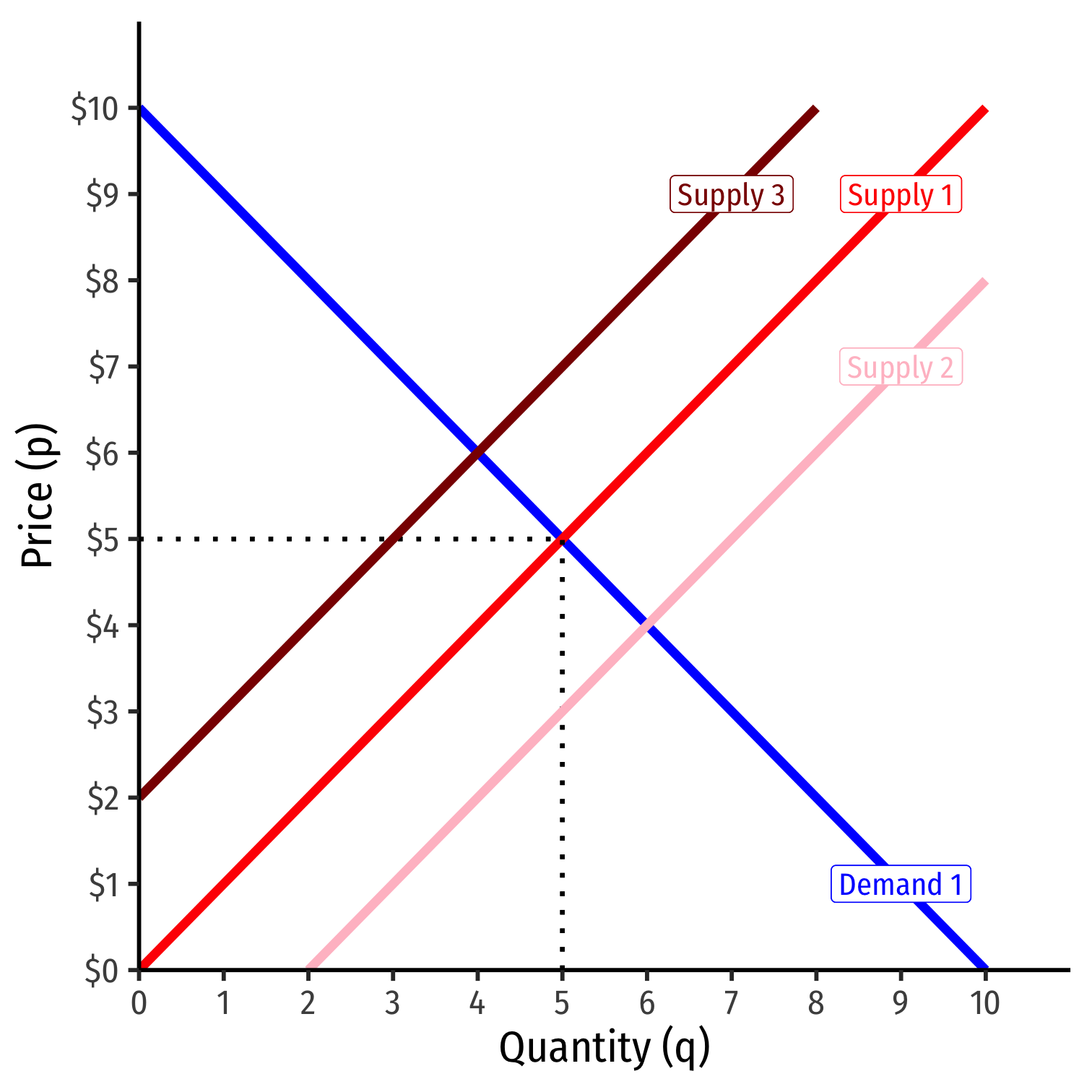

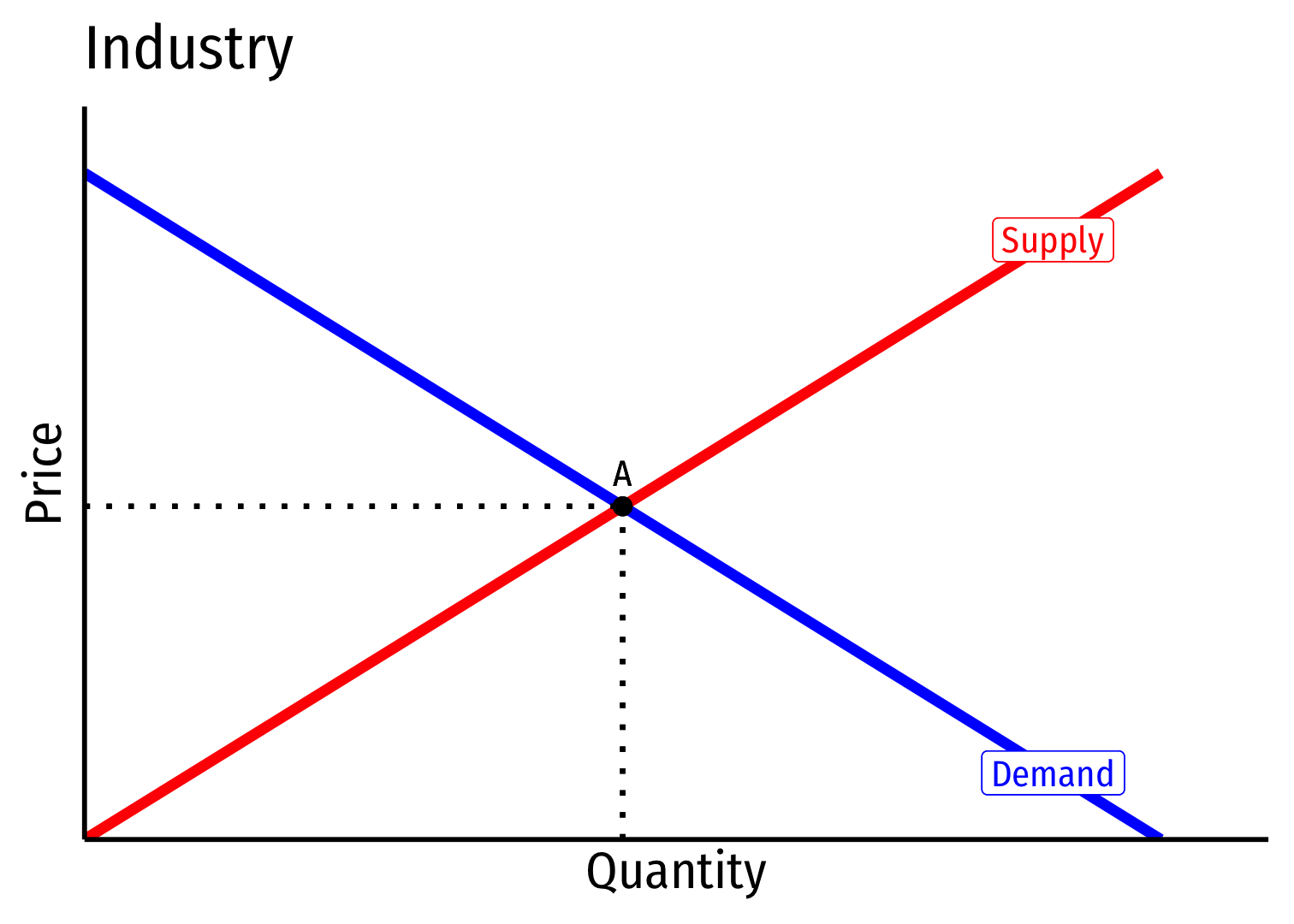

Entry/Exit Effects on Market Price

When all firms produce more/less; or firms enter or exit an industry, this affects the equilibrium market price

Think about basic supply & demand graphs:

- Entry: ↑ industry supply ⟹ ↑q,↓p

- Exit: ↓ industry supply ⟹ ↓q,↑p

If the size of the entire industry affects all individual firm’s costs, then there are external economies effects

- Cost externalities that spill over across all firms in an industry

External Economies I

Decreasing cost industry has external economies, costs fall for all firms in the industry as industry output increases (firms enter & incumbents produce more)

A downward sloping long-run industry supply curve!

Determinants:

- High fixed costs, low marginal costs

- Economies of scale

Examples: geographic clusters, public utilities, infrastructure, entertainment

Tends towards "natural" monopoly

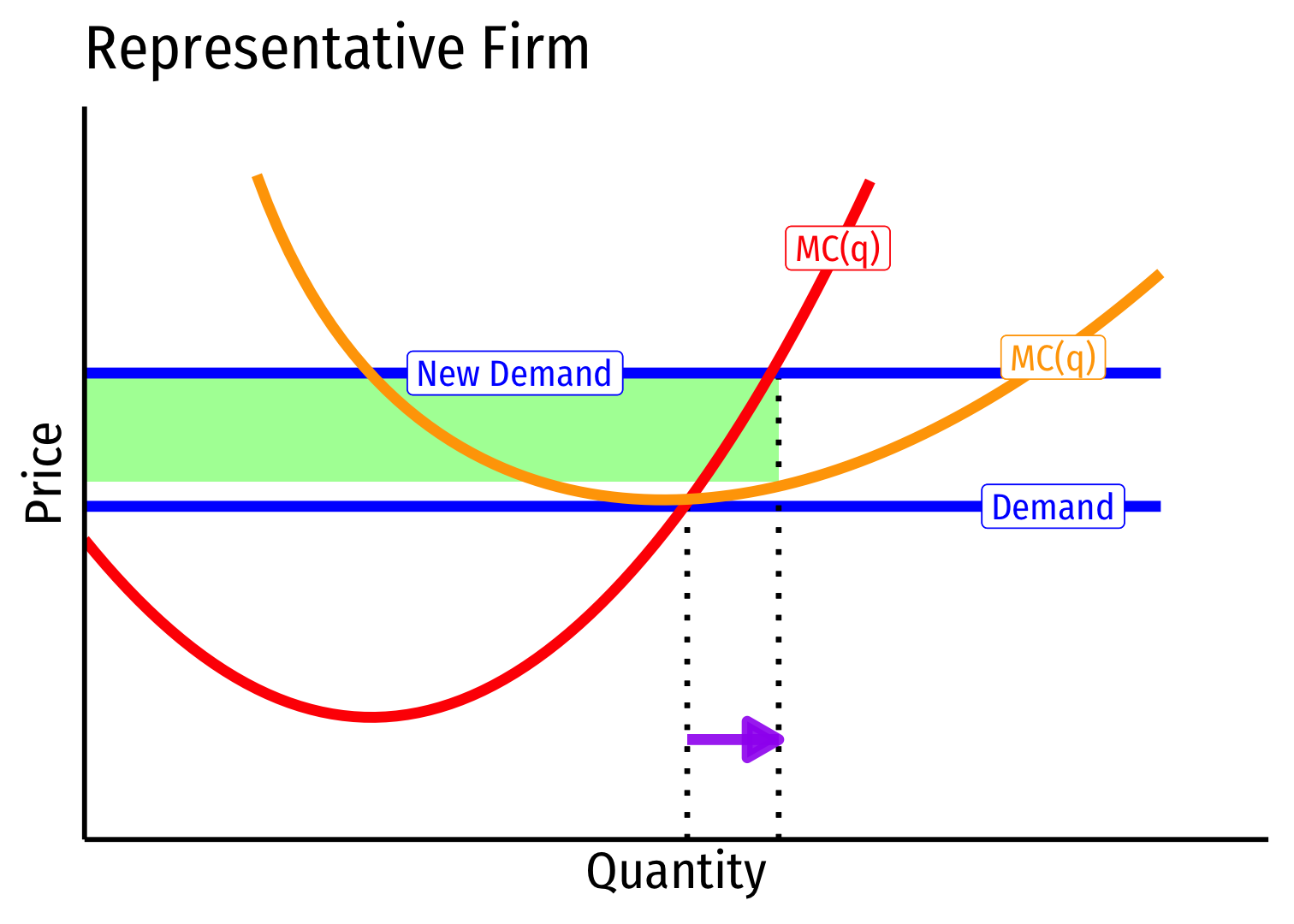

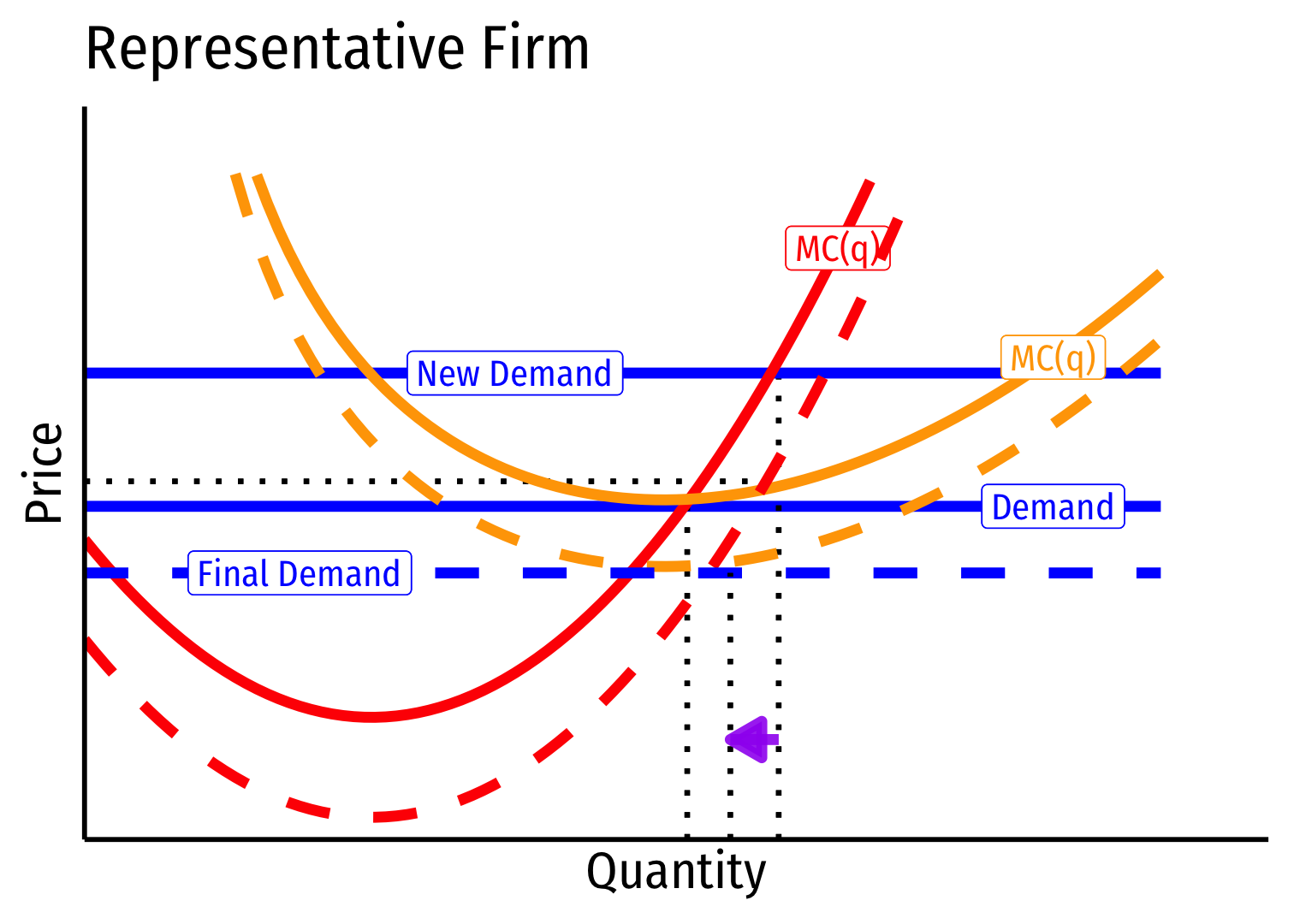

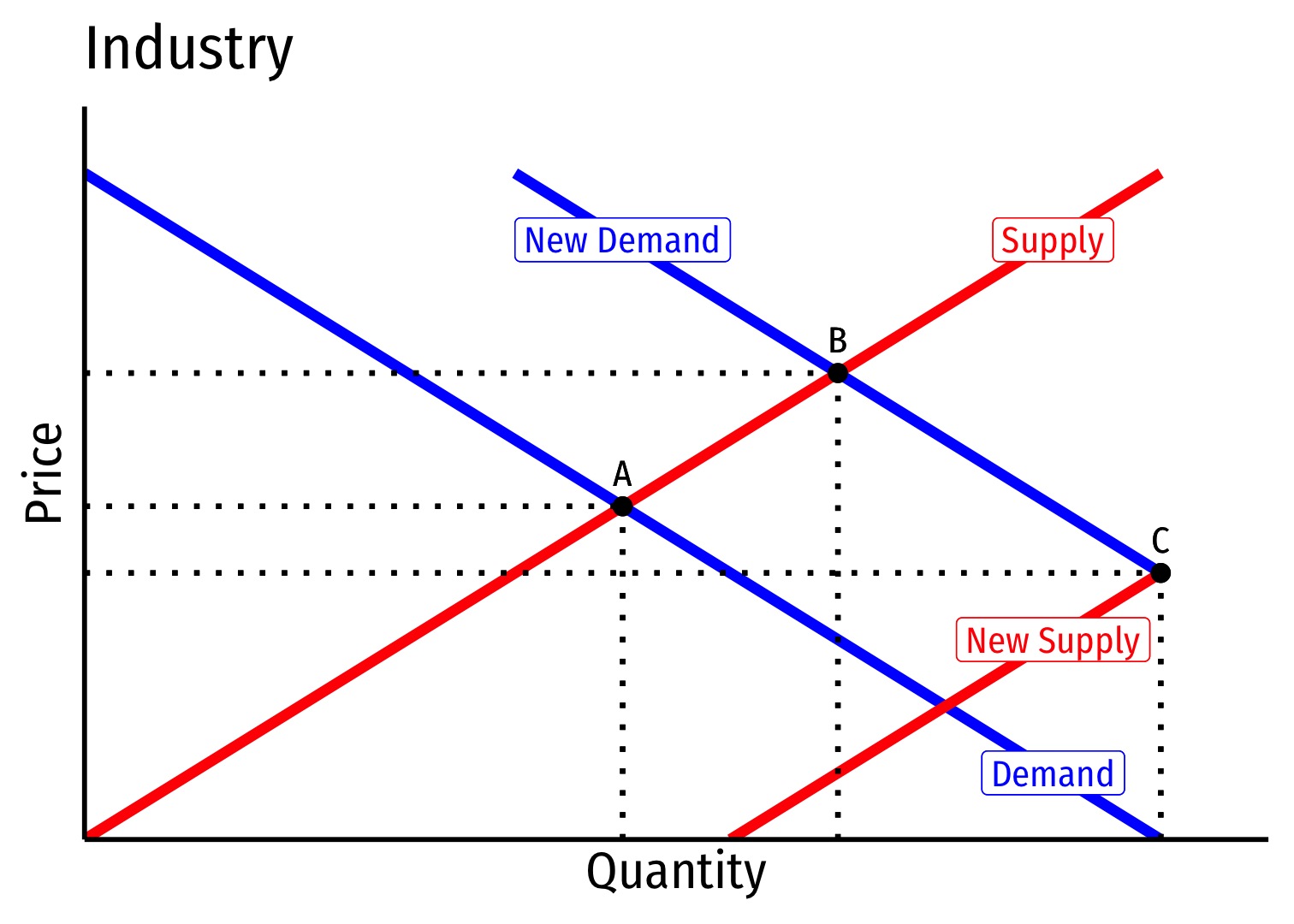

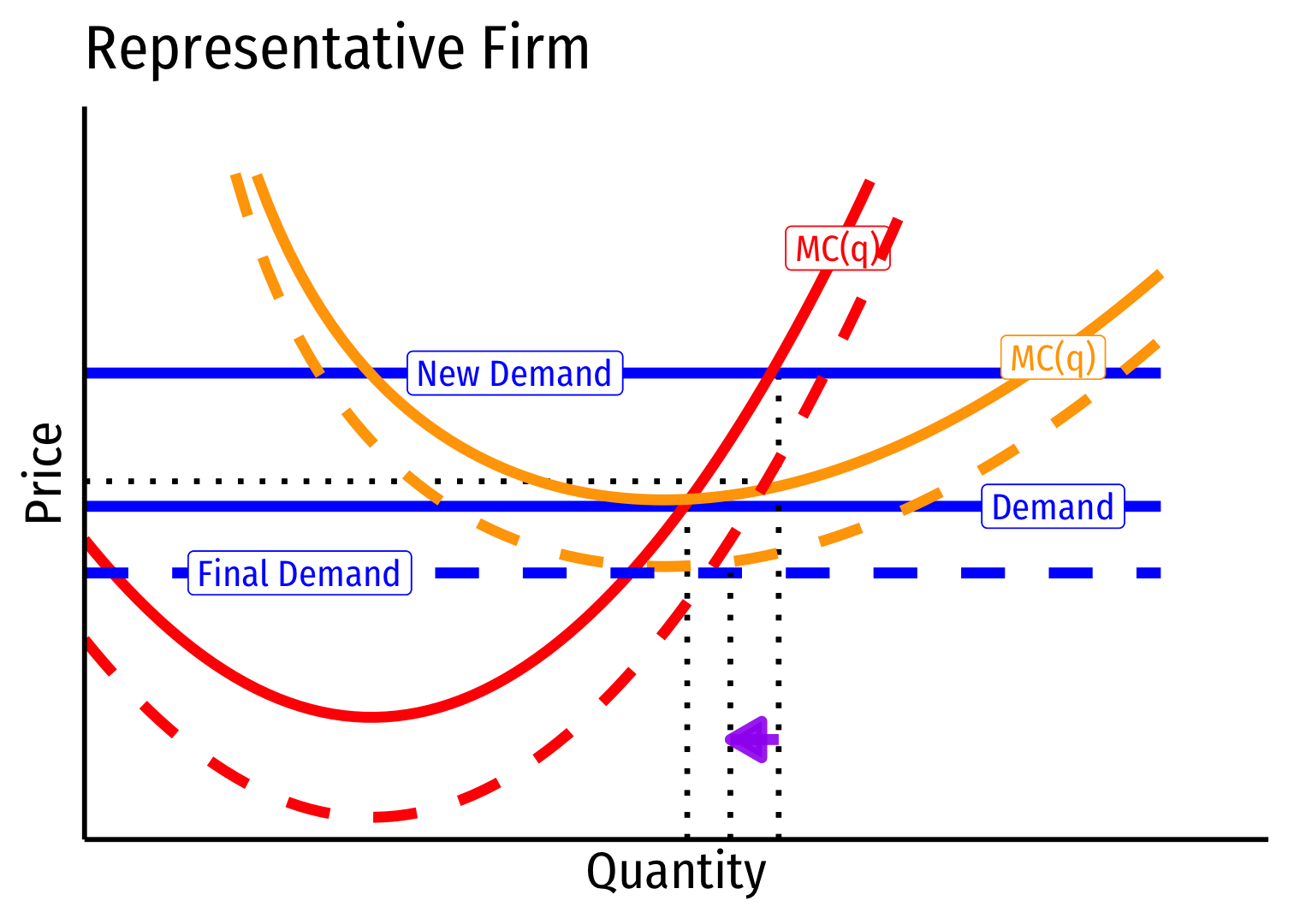

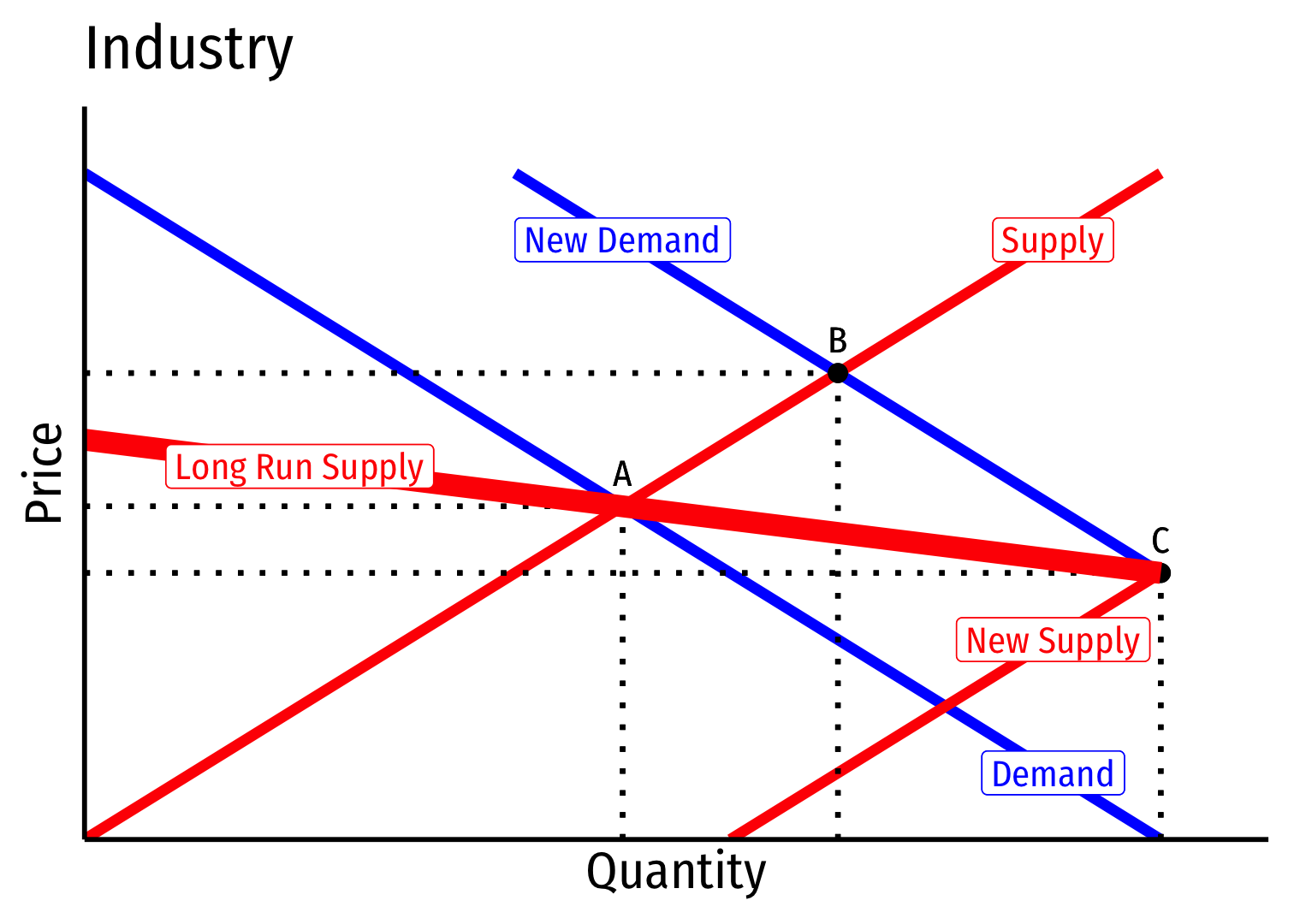

Decreasing Cost Industry (External Economies) II

- Industry equilibrium: firms earning normal π=0,p=MC(q)=AC(q)

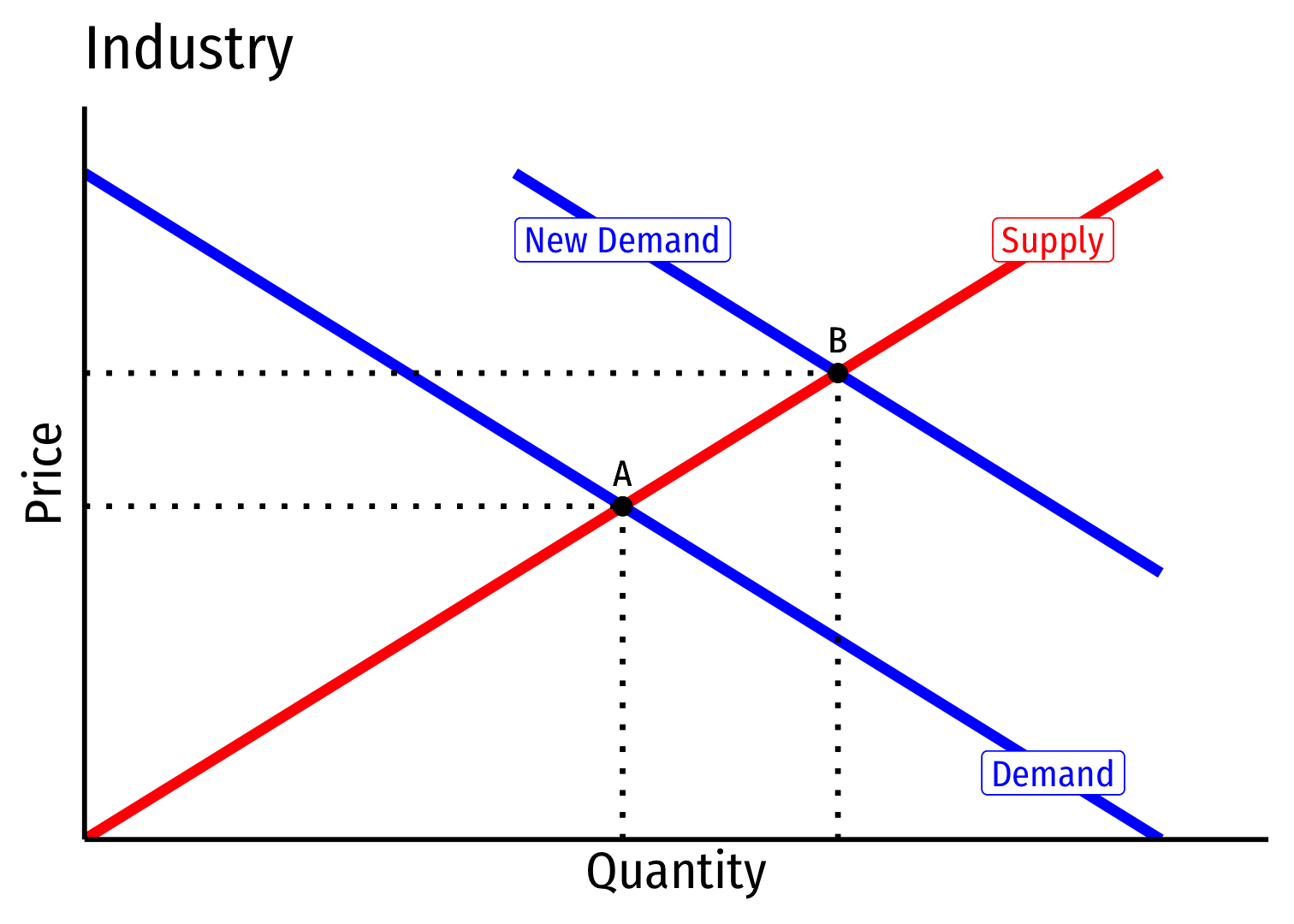

Decreasing Cost Industry (External Economies) III

Industry equilibrium: firms earning normal π=0,p=MC(q)=AC(q)

Exogenous increase in market demand

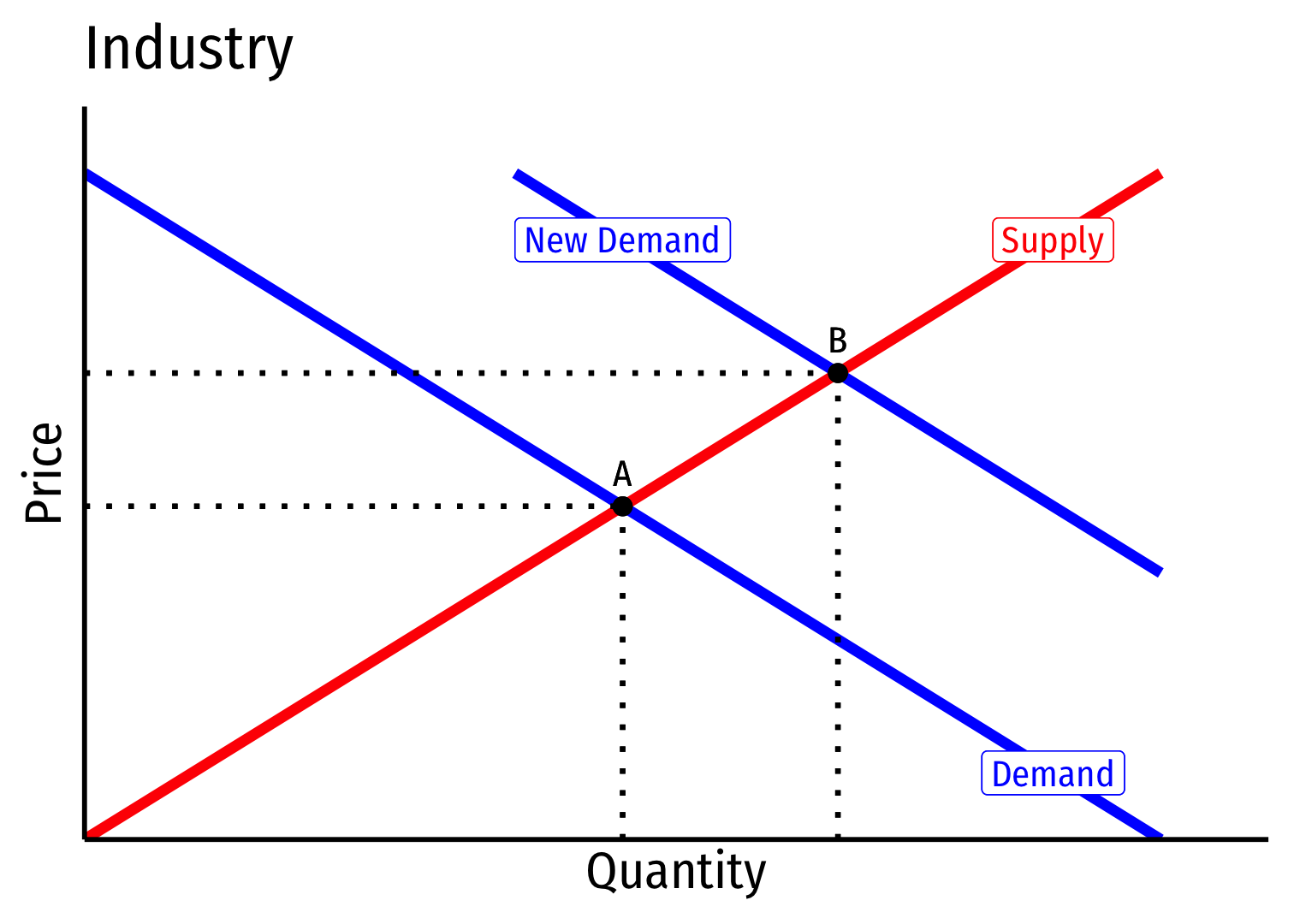

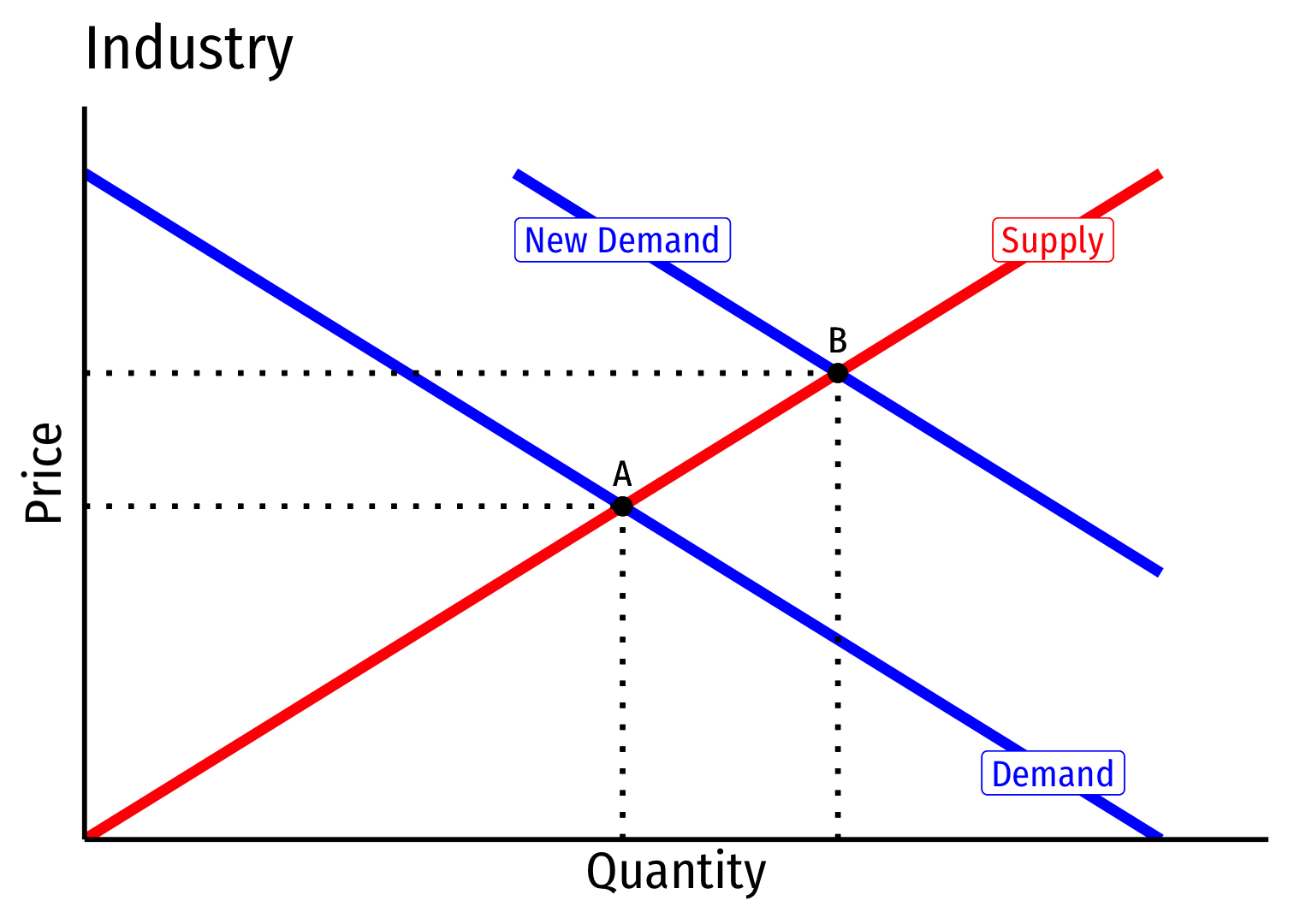

Decreasing Cost Industry (External Economies) IV

Short run (A→B): industry reaches new equilibrium

Firms charge higher p∗, produce more q∗, earn π

Decreasing Cost Industry (External Economies) V

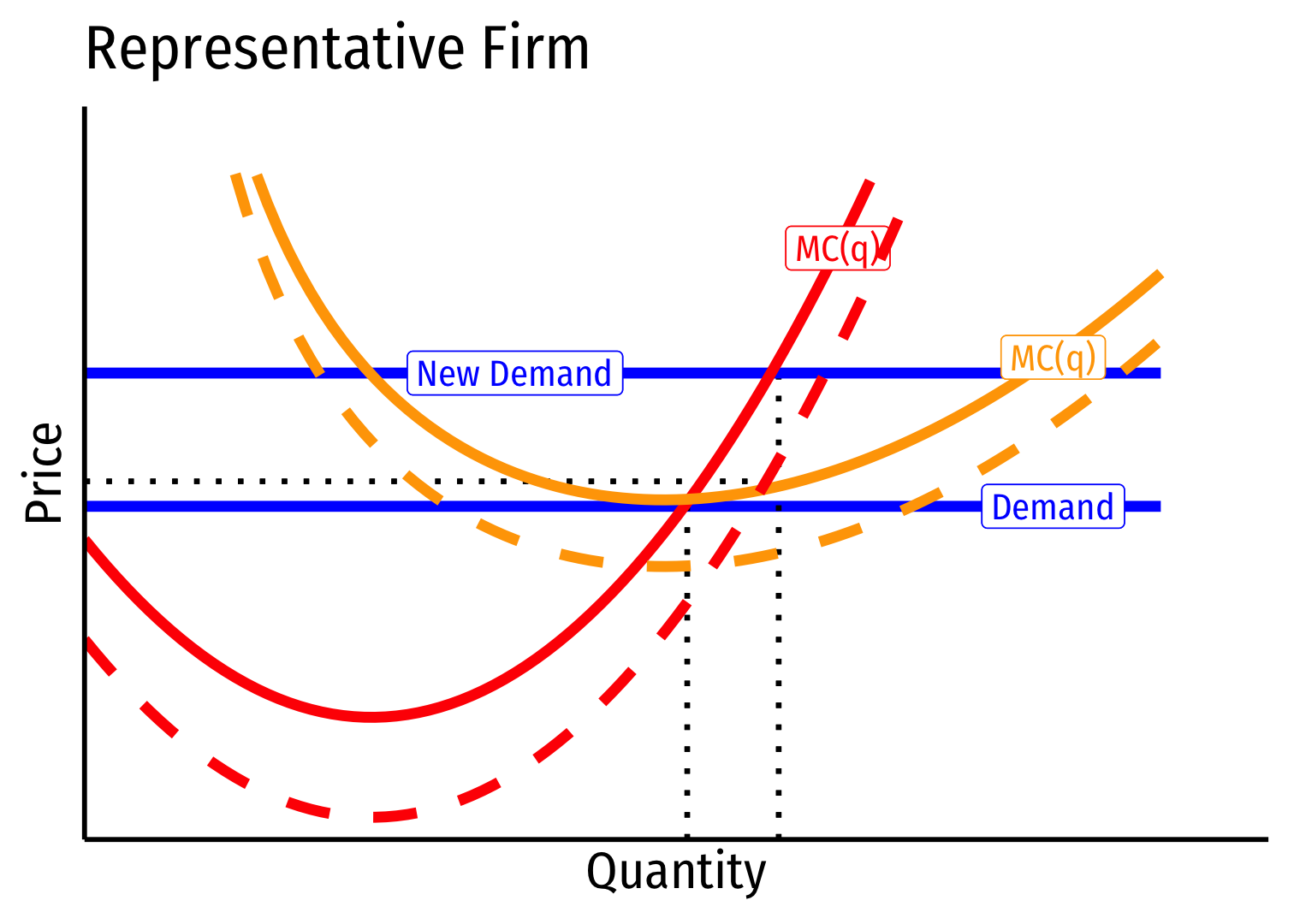

Long run: profit attracts entry ⟹ industry supply will increase

But more production lowers costs (MC,AC) for all firms in industry

Decreasing Cost Industry (External Economies) VI

Long run (B→C): firms enter until π=0 at p=AC(q)

Firms charge higher p∗, producer lower q∗, earn π=0

Decreasing Cost Industry (External Economies) VII

- Long run industry supply curve is downward sloping!

Internal vs. External Economies of Scale

Alfred Marshall

1842-1924

- Internal economies of scale:

“...are dependent on the resources of individual houses of business engaged in [the industry], on their organization and the efficiency of their management,” (p.220).

- External economies of scale:

“...are dependent on the general development of the industry [some of which] depend on the aggregate volume of production of the kind in the neighborhood while others again, especially those connected with the growth of knowledge and the progress of the arts, depend chiefly on the aggregate volume of production in the whole civilized world,” (p.220).

Internal vs. External Economies of Scale

Alfred Marshall

1842-1924

- What are some common sources of external economies?

- knowledge spillovers between firms

- subsidiary supplier industries

- local pools of skilled labor

“The most important of these result from the growth of correlated branches of industry which mutually assist one another, perhaps being concentrated in the same localities, but anyhow availing themselves of the modern facilities for communication offered by steam transport, by the telegraph and by the printing press,” (p.264).

Marshall, Alfred, 1890, Principles of Economics

External Economies: Geographic Clustering

150 Firms in Dalton, Georgia (pop. 33,000) supply over 70% of entire world’s carpet. Carpet has been made there since 1895.

External Economies: Geographic Clustering

990 firms in Hangji China (pop. 36,000) produce 3 billion toothbrushes a year, 80% of Chinese toothbrush production. Toothbrushes have been made there since 1827.

External Economies: Geographic Clustering

External Economies: Geographic Clustering

![]()

External Economies

Alfred Marshall

1842-1924

“[G]reat are the advantages which people following the same trade get from near neighborhood...The mysteries of the trade become no mysteries; but are as it were in the air, and children learn many of them unconsciously. Good work is rightly appreciated, inventions and improvement in machinery, in process and the general organization of the business have their merits promptly discussed: if one man starts a new idea, it is taken up by others and combined with suggestions of their own; and thus it becomes the source of further new ideas.”

Marshall, Alfred, 1890, Principles of Economics, Ch. 10

External Economies: Examples

“[In Silicon Valley] engineers left established semiconductor companies to start firms that manufactured capital goods such as diffusion ovens, step-and-repeat cameras, and testers, and materials and components such as photomasks, testing jigs, and specialized chemicals. . . . This independent equipment sector promoted the continuing formation of semiconductor firms by freeing individual producers from the expense of developing capital equipment internally and by spreading the costs of development. It also reinforced the tendency toward industrial localization, as most of these specialized inputs were not available elsewhere in the country.”

External Economies: Examples

“[In Silicon Valley] engineers left established semiconductor companies to start firms that manufactured capital goods such as diffusion ovens, step-and-repeat cameras, and testers, and materials and components such as photomasks, testing jigs, and specialized chemicals. . . . This independent equipment sector promoted the continuing formation of semiconductor firms by freeing individual producers from the expense of developing capital equipment internally and by spreading the costs of development. It also reinforced the tendency toward industrial localization, as most of these specialized inputs were not available elsewhere in the country.”

“it wasn’t that big a catastrophe to quit your job on Friday and have another job on Monday. . . . You didn’t even necessarily have to tell your wife. You just drove off in another direction on Monday morning”

Saxenian, Annalee, 1994, Regional Advantage. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, p.40

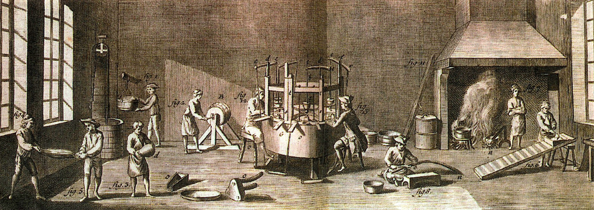

Division of Labor Strikes Back!

Adam Smith's pin factory illustration

Division of Labor Strikes Back!

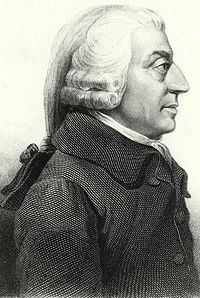

Adam Smith

1723-1790

"As it is the power of exchanging that gives occasion to the division of labour, so the extent of this division must always be limited by...the extent of the market. When the market is very small, no person can have any encouragement to dedicate himself entirely to one employment, for want of the power to exchange all that surplus part of the produce of his own labour, which is over and above his own consumption, for such parts of the produce of other men's labour as he has occasion for," (Book I, Chapter 3).

Smith, Adam, 1776, An Enquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations

From Perfect Competition to Monopolistic Competition

Economies of scale are inconsistent with perfect competition!

Requires us to drop an assumption of perfectly competitive markets

Instead, new trade theory begins with a foundation of monopolistic competition

We will begin next class with a review of this